- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Music’s solar plexus

- Article Subtitle: A guide for the Schoenberg-curious

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Arnold Schoenberg rarely missed a punch. Whether in music theory, composition, or the fraught polemics of his age, he communicated with a clarity of purpose verging on the tyrannical. Visiting Schoenberg in California during his last years, the conductor Robert Craft commented on ‘the danger of crossing the circle of his pride, for though his humility is fathomless it is also plated all the way down with a hubris of stainless steel’. Harvey Sachs is worried that music lovers of the twenty-first century are failing to appreciate the continuing significance of the composer despite, or perhaps because of, this armour-plating. Addressed to the musical ‘layman’, Sachs’s ‘interpretive study’ is a passionate, occasionally self-doubting essay intended to demonstrate why Schoenberg still matters. Schoenberg’s five chapters follow a chronological track, attempting to account for most of the fifty-odd opuses of Schoenberg’s oeuvre, within a rich context of his life’s turbulent course. His chapter titles dramatically reflect the struggle – battle lines, war, breakthrough, and breakaway – of both his life and his works. Sachs popularises, refreshes, and sometimes refutes the stainless-steel images passed down in the sanctioned texts of musicology, many written by Schoenberg’s acolytes.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Malcolm Gillies reviews 'Schoenberg: Why he matters' by Harvey Sachs

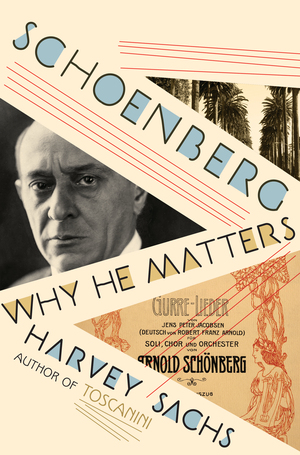

- Book 1 Title: Schoenberg

- Book 1 Subtitle: Why he matters

- Book 1 Biblio: Liveright, US$29.95 hb, 268 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Unfortunately, many other work commentaries read as hurried program notes, and some swaths of the output are largely overflown: Opp. 25-29 (1921–26) and the final Opp. 47–50c (1949–51). But he frequently lightens the reader’s burden with asides outlining his own struggles in comprehension or why he favours some recordings over others. Sachs also gives good coverage to several substantial but incomplete works, such as the oratorio Die Jakobsleiter (Jacob’s Ladder) and the opera Moses und Aaron. But he wisely warns that he is ‘Schoenberg-curious’ and a storyteller, rather than an analytical expert.

Sachs’s account of Schoenberg’s life, sandwiched between these many work commentaries, draws particular attention to his Jewish to Lutheran conversion, then, in 1933, his Jewish reconversion and its effect upon his compositions, libretti, essays, and public stances. It also nicely sketches the different types of lives he was forced to live, across two marriages and different friendship groups, in Vienna, Berlin, New York, and Los Angeles. A recurring theme in all venues is his career’s dedication to teaching, resulting in half a dozen stunningly perceptive music theory books (‘I have learned this book from my pupils,’ Schoenberg once confessed) and an unparalleled list of famous alumni: composers (including Alban Berg, Anton Webern, John Cage), performers (violinist Rudolf Kolisch, pianists Rudolf Serkin and Eduard Steuermann), musicologists (Paul Pisk, Josef Rufer), and even baseball legend Jackie Robinson. Indeed, it was Sibelius who cheekily suggested that Schoenberg’s greatest works were his students. It is a pity that Sachs makes scant reference to the compendium Style and Idea (1950), where Schoenberg’s conceptual brilliance and verbal acuity speak volumes.

So, having read Sachs’s five works-amid-life chapters, why does Schoenberg matter? In his short Prologue, Sachs expresses dismay at the dwindling performances of Schoenberg’s works, and asserts his belief that despite Schoenberg’s ‘thorny’ character and works, he ‘must be confronted by anyone interested in the past, the present, and the future of Western art music’. When reaching his seventeen-page Epilogue, ‘What Now?’, any reader will be unsure exactly where Sachs’s proposition stands. The book’s overwhelming message has been that most listeners, including professional musicians, did not, do not, and probably never will appreciate Schoenberg’s music, especially his atonal and serial works. The barrier lies in connecting understanding of music’s inner workings to what listeners are hearing. ‘This is perfectly reasonable,’ comments Sachs. The final pages of his Epilogue climb down from his Prologue’s bold assertion. Sachs acknowledges that many of Schoenberg’s works ‘require repeated hearings and a great deal of focus, which most listeners haven’t the time or the desire to dedicate to them’. At most, he concludes, the gems of Schoenberg’s various periods ‘deserve the attention of any serious music lover’.

My problem with Sachs’s proposition, both in the Prologue’s assertive form and the Epilogue’s deserving form, starts with his opening observation that Schoenberg’s works are not much programmed these days. This is made on the basis of a ‘random glance’ (Sachs’s words) at one recent season’s programming across six major orchestras on both sides of the Atlantic. It needed much more investigation, and a much broader sample space, to elicit any conviction. His own difficulties in appreciating much of Schoenberg’s later output, and anecdotes about problems of memorising his music, are not necessarily shared by a younger, often more proficient community of musicians and music lovers, now spread virtually across the world. His opening pessimism is, I feel, misplaced. Schoenberg’s music lives. His theoretical ideas flourish. Sachs’s book can only encourage the zeal of many, who will still opt to be ‘confronted’ by Schoenberg’s many challenges, and disprove his ‘random glance’.

Comments powered by CComment