- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Law

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lacerated feelings

- Article Subtitle: A feminist history of love and the law

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 2023, a broken engagement might be followed by tears, the division of possessions, and a reliance on family and friends. It might even involve a few trips to the therapist. But up until the mid-to-late twentieth century, Australian men and women’s heartbreaks could also see them take a trip to court to charge their partner with breach of promise of marriage.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Zoe Smith reviews 'Courting: An intimate history of love and the law' by Alecia Simmonds

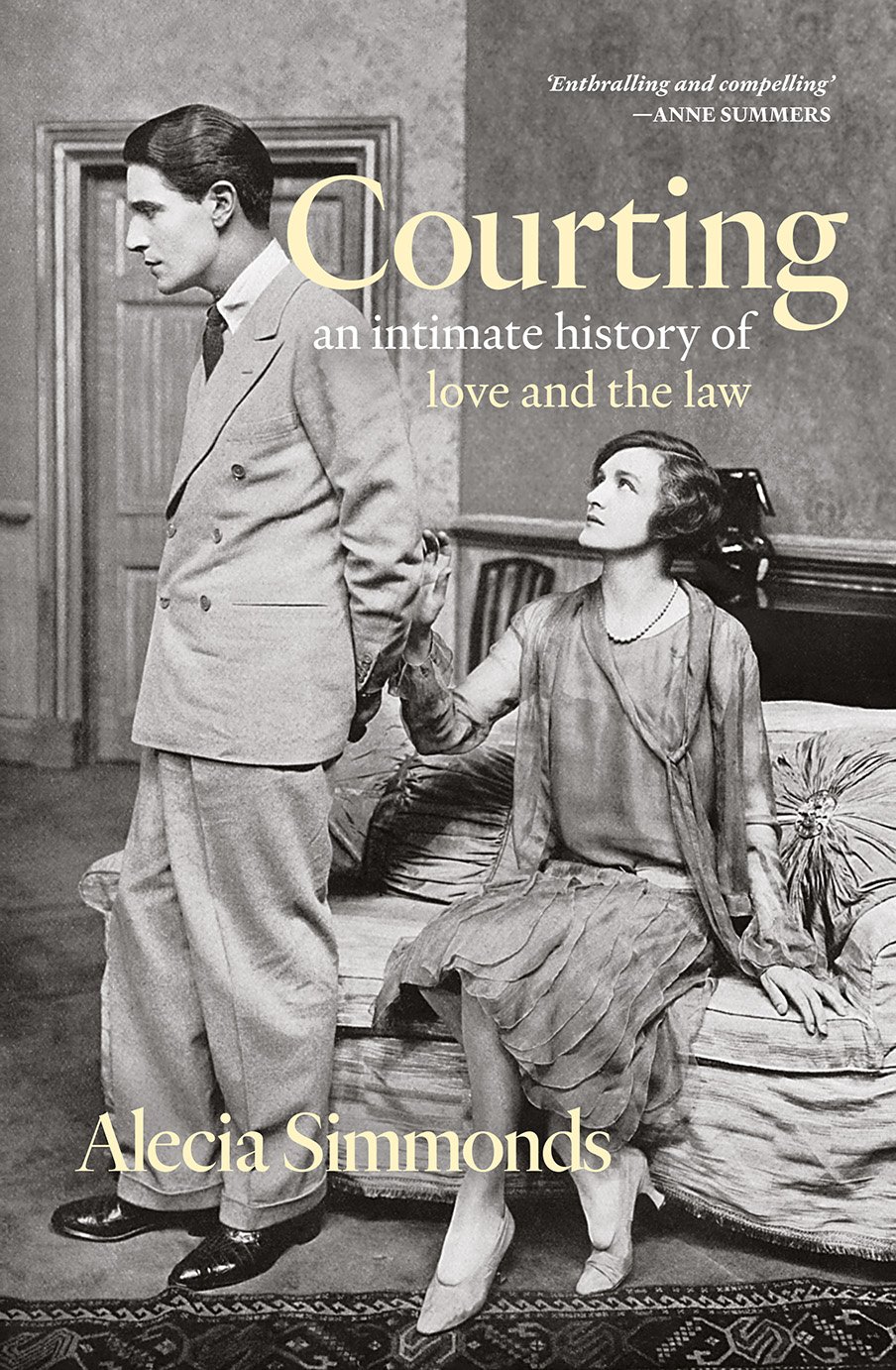

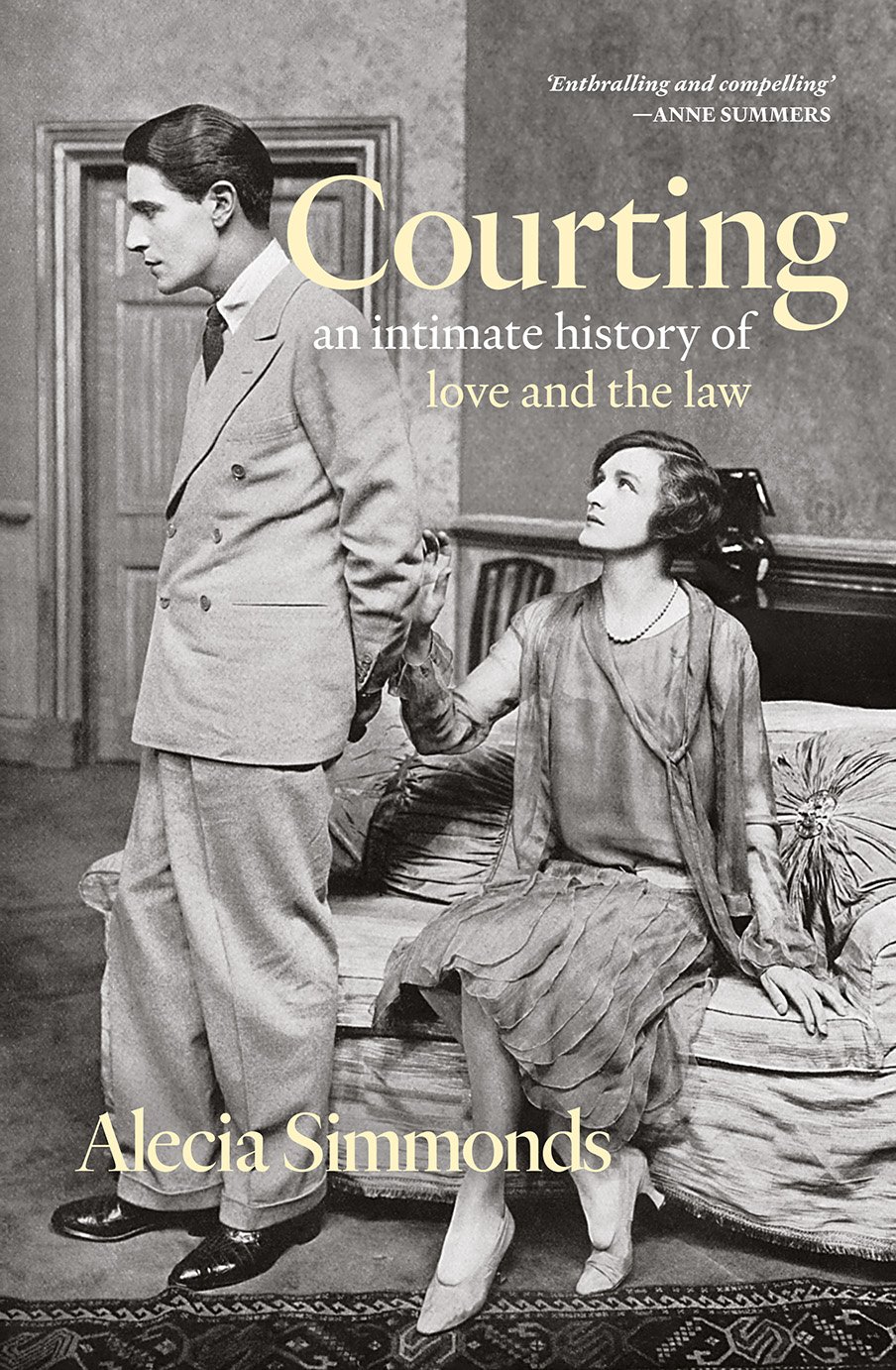

- Book 1 Title: Courting

- Book 1 Subtitle: An intimate history of love and the law

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $45 pb, 440 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Simmonds first introduces us to Harriet Sutton, who, in 1806, fled her domestic-service role dressed as a man to meet her fiancé, Adolarius Humphrey, the government mineralogist for New South Wales. He would then declare her convict parentage an impenetrable barrier to their marriage, revealing the influence of class and convictism on romance in a settler colony.

Our encounter with James Lucas (formerly Jamsetjee Sorabjee), in 1892 – the first Australian interracial breach of promise and a rare case with a male plaintiff – exposes how race was con-structed through romance and the tensions between the two. The 1916 case brought by Verona Rodriguez divulges the influence of consumer culture and women’s growing financial autonomy on romantic love during the early twentieth century, as they begin to claim both lost wages and compensation for their trousseaus in the wake of their abandonment by men.

The case studies also reveal the diverse damages plaintiffs claimed from their former lovers, seeking remuneration for rent unpaid by their partners’ families, for their domestic labour and care, for the money spent on a ring, for a damaged reputation, and for the loss of a potential home and secure future – telling us much about the historical valuation and economics of love.

Interwoven throughout these cases is Simmonds’s astute examination of the patriarchal legal system and women’s navigation of it. As Simmonds highlights, breach of promise of marriage was the only civil suit that demanded women’s evidence be corroborated, legally codifying a patriarchal mistrust of women’s evidence in a suit predominantly filed by lower-middle-class women.

In a shocking example of this, Ilma Vaughan’s case reveals how coverture extended into courtship. Coverture was a legal doctrine that denied married women an independent legal identity and which gave husbands a legal immunity to beat, rape, or economically abuse their wives. Ilma used her 1891 breach of promise suit against popular politician Myles MacRae to protest his rape of her, only months after his wife, Clara, had successfully divorced him for considerable domestic violence and adultery. Yet the court argued that Miles’s rape of Ilma was ‘justified’ due to their engagement – her engagement ring signified his total ownership of her.

The long shadow of coverture, even following changes to married women’s legal status via shifting property ownership and divorce laws, reveals itself again in the 1938 case of Robina Allan and Frederick Growden. Frederick’s physical abuse of Robina was deliberately twisted to mark her as the aggressor in a legal arena presided over entirely by men, which increasingly punished angry women and affirmed male violence and entitlement.

With women’s economic and social dependence upon marriage the raison d’être of breach of promise, the suit affirmed and relied upon female fragility and passivity. The final three case studies of the book particularly demonstrate how women’s growing political and economic freedoms were increasingly subjected to the discipline of judges. Female plaintiffs, the vast majority of whom had won their cases in the nineteenth century, began to lose. With twentieth-century women suffering less in a material sense than their Victorian predecessors, due to their ability to work and find another partner without a permanently ruined reputation, the court demanded they prove emotional turmoil sufficient to warrant medical, and legal, intervention.

As a result of this shift towards medicalising and pathologising heartbreak, Simmonds identifies a decline in breach of promise suits. She explains how the rise of psychology following World War I influenced discourses surrounding heartbreak as ‘returned soldiers and jilted plaintiffs began to report remarkably similar symptoms’. While the medicalisation of heartbreak assisted some women in their cases, psychological developments and the rise of the counsellor meant that by the 1950s not only were heartbroken women bearing the burden of a relationship’s failure, but legal options for courting couples were broadly frowned upon and women charting this path risked being labelled ‘abnormal’.

By the time breach of promise was formally abolished in 1976, many had already moved away from the courtroom and into the offices of counsellors and psychologists to air their wounded feelings and broken hearts. It was not entirely abandoned – then Labor MP Paul Keating was sued for breach of promise in the early 1970s, with the case later weaponised against him in parliamentary debate – but by 1976, the action’s economic foundations and cultural acceptability had eroded.

So, what is it that we can draw from the nearly one thousand cases of breach of promise of marriage over almost two centuries? Simmonds argues that women’s pursuit of such suits produced ‘feminist political subjects’. ‘The women who sued their lovers wielded the suit in profoundly feminist ways,’ she maintains, ‘refusing their victim-status by aggressively prosecuting for economic and emotional injuries suffered, advancing feminist arguments around the labour of care, protesting sexual violence, and demanding an ethics of relationship.’ In Simmond’s masterful management of these women’s poems, scraps of lace, nightgowns, letters, and tears, we find a feminist history of love and the law exposed from within a Victorian relic of female legal victimhood.

Comments powered by CComment