- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: India

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dosti and the diaspora

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s overdue interest in India

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In April 1990, Australia’s high commissioner to New Delhi, Graham Feakes, was in the final year of a six-year posting. Still regarded as one of Australia’s finest diplomats, he had worked tirelessly to invigorate a relationship that had been allowed to drift aimlessly for decades. Under his watch, in 1986 Rajiv Gandhi made the first visit by an Indian prime minister to Australia in almost two decades. Bob Hawke reciprocated shortly afterwards. Ministerial commissions and senior level officials’ groups were established. Aid was set to increase.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

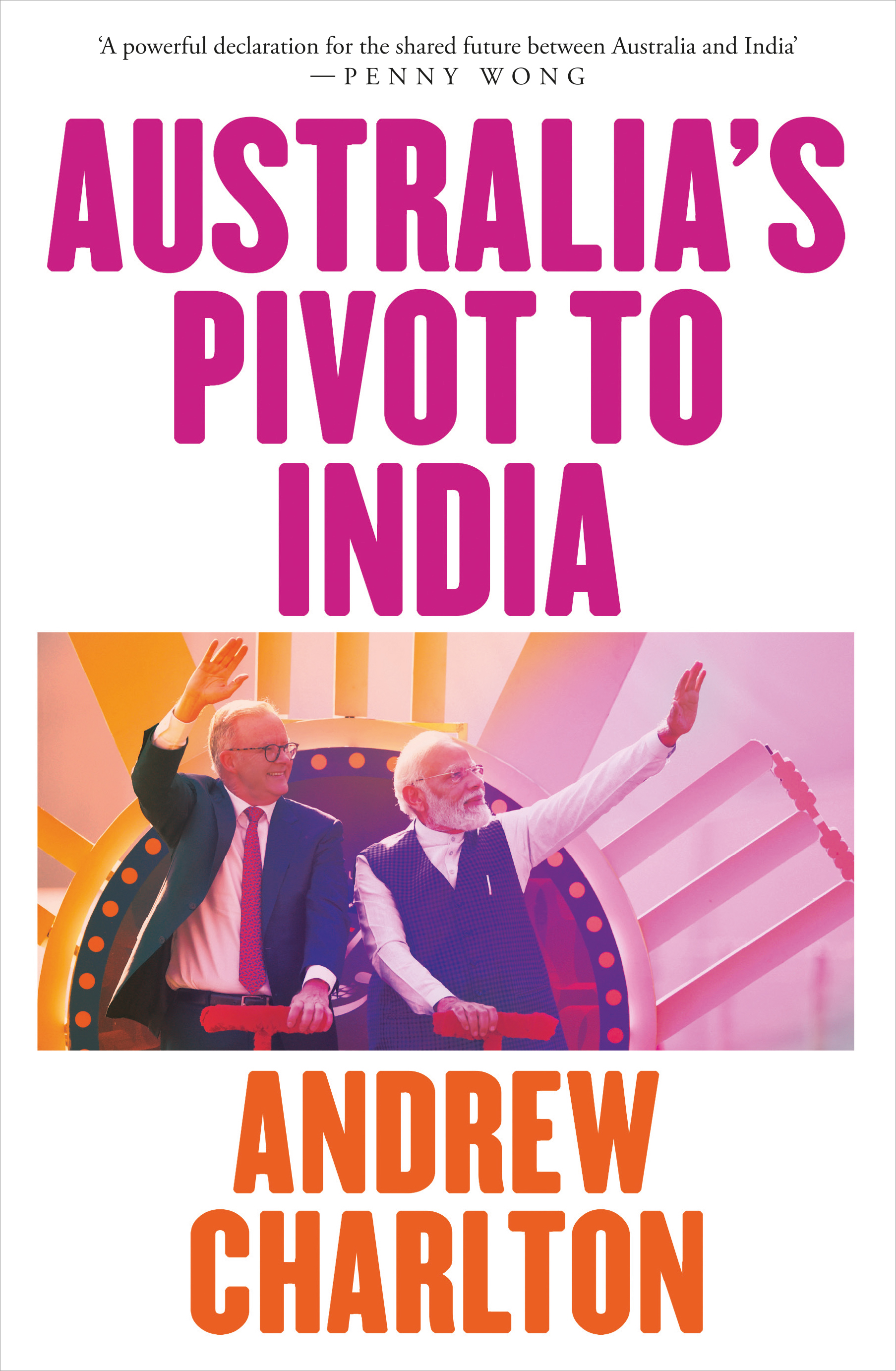

- Article Hero Image Caption: Anthony Albanese and Narendra Modi in New Delhi, 2023 (photograph by Sondeep Shankar/ Pacific Press Media Production Corp/Alamy Live News)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): John Zubrzycki reviews 'Australia’s Pivot to India' by Andrew Charlton

- Book 1 Title: Australia's Pivot to India

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 253 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Andrew Charlton, in his book Australia’s Pivot to India, also refers to the Mirage sale in the chapter ‘Setbacks and Squalls’. The list of reversals is a long one – the Morrison government’s Indian travel ban during the Covid-19 crisis being one of the most recent. And there will be more. Charlton’s book came out before India’s diplomatic spat with Canada over claims that the Indian government was behind the assassination of a Sikh separatist leader on Canadian soil, an allegation that India has steadfastly denied. Australia and Canada share intelligence as part of the Five Eyes alliance, so it came as no surprise when ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess publicly backed Canada’s allegation. In the past, Australian diplomats might have joined dozens of their Canadian counterparts, who were told to pack their bags. That a major squall was averted reflects the work India and Australia have put into strengthening the bilateral relationship.

As the Labor member for the federal seat of Parramatta, home to one of Australia’s largest Indian diasporic communities, Charlton is well placed to chart the changing dynamics of the relationship. Breezy in style, peppered with anecdotes drawn from his personal interactions with his constituents and copious graphs and tables, his book is timely. Anthony Albanese made two visits to India in 2023, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi received a rock-star-like reception when he addressed a mainly Indian crowd at Sydney’s Qudos Bank Arena in May. Trade is booming and defence ties are expanding. Both countries are enlarging their diplomatic footprints, with Australia opening a new consulate in Bengaluru, and India adding Brisbane to its portfolio.

Australia and India, together with the United States and Japan, are members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or the Quad, which is intended to enhance regional security (and to counter the rise of China, though this aim is never stated). With more than a million Indians now in Australia, people-to-people ties have never been stronger. India’s GDP growth is the second fastest in the G20, putting it on track to become the third-largest economy in the world by the end of the decade. Now the world’s most populous nation, India is being touted as the next global superpower.

As Charlton acknowledges, the Australia-India relationship is tracking at nowhere near its full potential. Australian investment in India has been stuck at around a fifth of the flow to China. An Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement signed last year is likely to fall short of its objectives, thanks to a raft of protectionist measures introduced by the Indian government to shield local industry. Perceptions remain a problem. India’s ranking on the Lowy Institute’s ‘feeling thermometer’, which rates Australians’ warmth towards other countries, fell from sixth in 2006 to sixteenth in 2022, only higher than Russia, China, Myanmar, and Afghanistan.

Much of the reason for this is historical. The White Australia policy, Canberra’s closeness to Washington, and a myopic obsession among government and business leaders who believed that China was the key to Australia’s future, relegated India to the sidelines of Australian foreign policy. It would take until 2012 and the Gillard Labor government’s decision to overturn a 1977 ban on uranium sales to India before relations began to improve. Gillard’s Australia in the Asian Century White Paper identified India as one of the five regional nations of prime importance to Australia, and proposed making Hindi one of four priority languages in Australian schools. In 2018, Peter Varghese, a former high commissioner to India, authored the landmark report An India Economic Strategy to 2035, which made the case that no other country offered Australia the same economic opportunities. At last, as Charlton declares, Australia and India were able to ‘pivot’ past the tired references to the ‘Three C’s’ of Commonwealth, curry, and cricket to the ‘Four D’s’ of democracy, defence, dosti (friendship), and the diaspora.

Charlton, however, neatly sidesteps the other ‘pivot’: namely, the drift towards Hindu majoritarianism under the Modi government and the increasingly illiberal nature of India’s democracy. This pivot, which manifests itself in the persecution of minorities and attacks on civil society groups and independent journalism, is virtually ignored. Another serious omission is Charlton’s failure to acknowledge and therefore address the low level of India literacy within Australia. In 2022, there were only two universities running South Asia programs, down from thirteen in the mid-1990s. As a recent University of Melbourne report noted, the number of fluent Hindi speakers of non-South Asian origin in Australia can be counted on the fingers of two hands.

Despite these drawbacks, Charlton’s book makes a much-needed case for placing India at the forefront of Australia’s Indo-Pacific strategy. What were once ‘fundamentally incongruent outlooks on the world’ have evolved into multiple spheres for partnership. A better resourced bureaucracy and closer coordination across agencies make another Mirage debacle less likely. The foundations have been laid and decades of complacency put to rest. Australia’s long-overdue pivot to India is finally becoming a reality.

Comments powered by CComment