- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A thousand strangers

- Article Subtitle: A prodigious history of a battalion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is an honoured tradition of battalion histories in Australia, particularly from World War I. The best of them tell us something of the individuals who served Australia well. This book takes battalion histories to an entirely new level. It is the most complete, and the most absorbing, account of a battalion I have ever read.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael McKernan reviews 'Men at War: Australia, Syria, Java 1940–1942' by James Mitchell

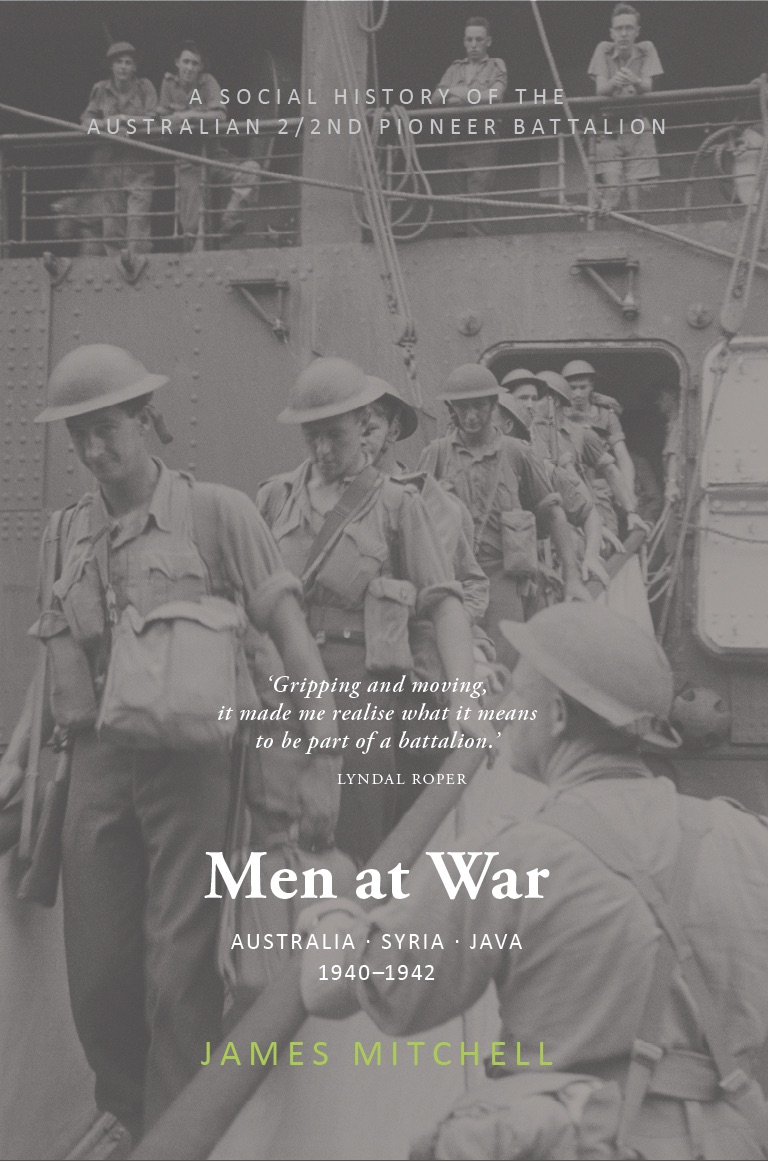

- Book 1 Title: Men at War

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia, Syria, Java 1940–1942

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $49.99 hb, 643 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The research is prodigious. Mitchell has looked everywhere and found gems in unexpected places. Readers will be often surprised at some of the things Mitchell discovered. For example, I thought I knew well the mechanism for the delivery of casualty telegrams to bereaved households in both world wars. Clergymen did it in World War I but surrendered that responsibility in World War II to the Post Office. I did not know that Robert Menzies, as prime minister, wrote to state premiers inviting them to ask local councils to find out what the people wanted and to implement their suggestions. How sensitive and how caring of Menzies. Different solutions suited different communities.

After such a long introduction to the business of war, readers might begin to wonder if Mitchell has the ability to write about battle. They will come to his account of the Syrian campaign with some impatience and some fascination. Under the command of Brigadier F.H. Berryman, the Australian and British forces were tasked with expelling the French (Vichy) forces from Syria and thus preventing a German landing there.

Who knew the campaign was so botched? Coming right after the Greece and Crete campaigns, terrible disasters for Australia, few Australians have paid much attention to Syria. The mistakes made by the senior leadership – take a bow Frank Berryman – are nearly unbelievable and, usually, not examined in detail in earlier books.

Incredibly meagre armaments were sent to Syria in support of the troops and there were no aircraft available for the operation. The Australians were initially encouraged to wear their slouch hats into battle to convince their French opponents that they were the same lovable Aussies of 1916–18, the leaders expecting that the enemy would then surrender. No such luck. Never go into battle on wishful thinking.

Sending the battalion to overrun the key objective, Fort Merdjayoun, with rifles and little else was insanity; it resulted in large loss of life for the battalion and many other serious casualties. It may be argued that Berryman had few other options, so poorly equipped were the Pioneers, but if he did not foresee the disaster in advance, he should have. Historians have rightly condemned the First Battle of Bullecourt (1917) as a sad waste of excellent troops and a byword for poor planning. Merdjayoun was a tragic further example of this.

Mitchell cares deeply about the waste of life this action caused; he writes with passion and anger about what the Pioneers suffered. Their own commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Nelson Wellington, wonderfully known as ‘Nellie’ by his troops, starred in creating his battalion in Australia, but was a woefully deficient commander in action. At least he was replaced.

The poor Pioneers, though the French eventually surrendered and the campaign was won, had suffered the near-destruction of their battalion. They regrouped, integrated their reinforcements and awaited orders. Sadly, their second campaign of the war, Java, saddled them again with poor leadership and a near-criminal lack of equipment. The battalion in Egypt was loaded on to one ship; all their gear and equipment on to another, which failed to arrive in Java. Did anyone in charge in Australia know this and seek to stop the campaign before it began?

Imagine a few hundred men going up against a crack Japanese division, approximately 10,000 men, the Pioneers with rifles and about fifty rounds of ammunition per man. Individual junior leaders had to scrounge around the wharves for vehicles and the other necessities for fighting against a skilled and determined opponent.

Mitchell emphasises the fighting spirit of the Pioneers and their success in holding up the Japanese for a few days. One of the soldiers summed it up: ‘Java was a stunt, but anyhow it worked, held them up long enough for the Yanks to get into Australia.’ And, adds Mitchell, while the Pioneers fought and died on Java, two Australian divisions were on the Indian ocean on their way back to Australia for its defence. He writes: ‘the great gift the Pioneers gave to their mates was to keep Japanese eyes focused on Java.’ The outcome was that almost every single one of the surviving 2/2nd Australian Pioneer Battalion (a few hundred men) became a prisoner of war in the hands of the Japanese.

This book was a labour of love for a skilled and senior historian who is the son, nephew, and godson of Pioneers. He has pursued his task with extraordinary diligence, giving the Pioneers the humanity and the recognition they so richly deserve. Men at War is beautifully produced, clearly and elegantly written, with easy explanations of every technical and military term to help the reader. Every statement is sourced, and there is a rich index to help readers reread crucial sections and hunt out interesting men.

This long book kept my interest throughout. It surprised me to learn so many new things about matters I thought, erroneously, I already understood. Men at War, if not quite a masterpiece, is in the first rank of Australian military historical writing. Let us hope it inspires many imitators.

Comments powered by CComment