- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: So-called Australia

- Article Subtitle: Of monuments and mythuments

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

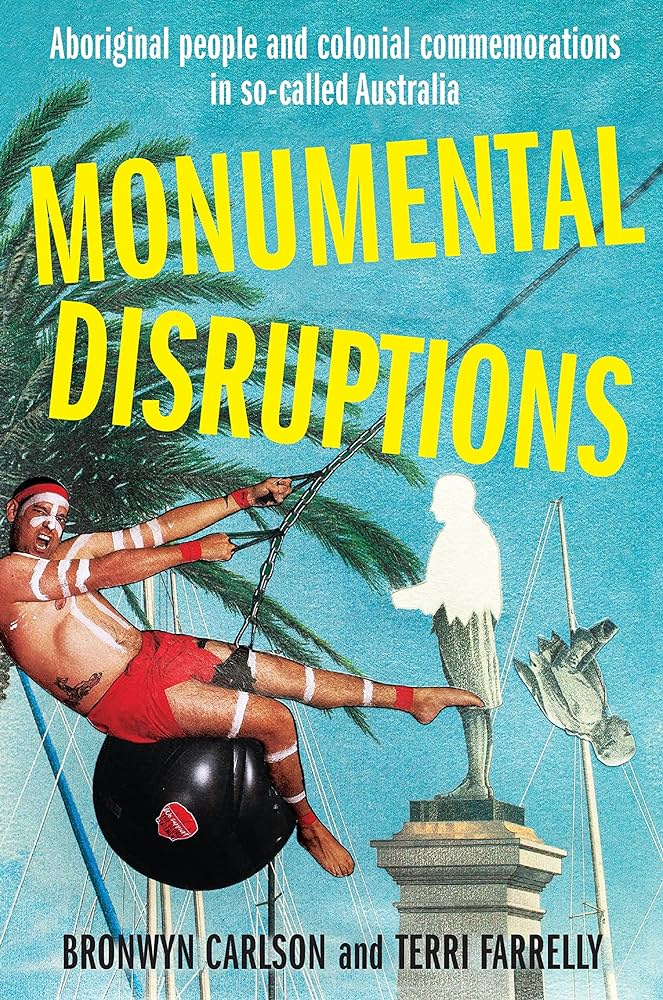

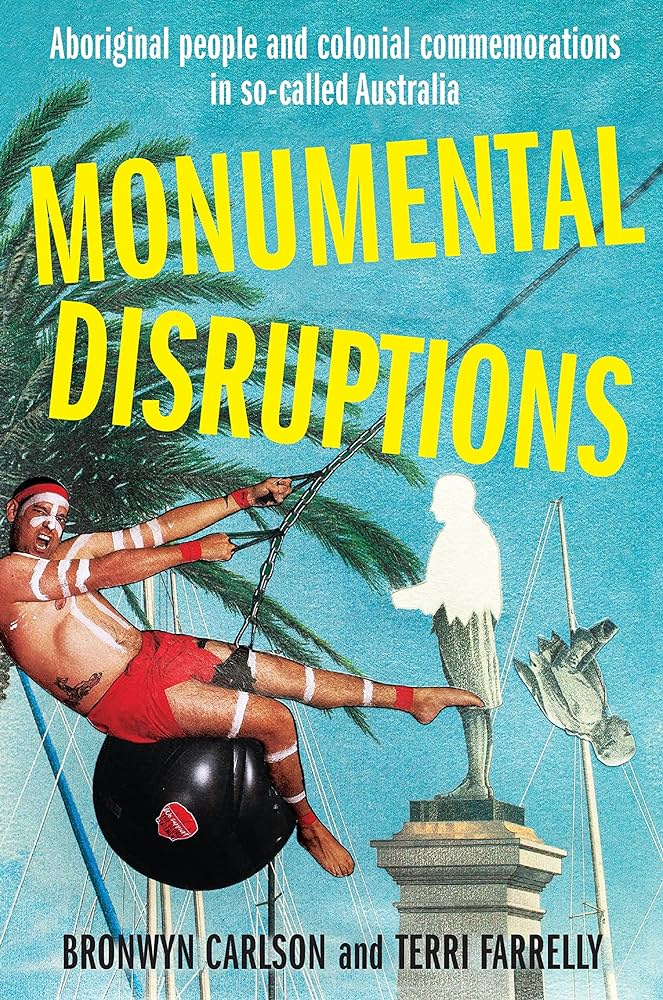

Monumental Disruptions could not be more timely. Bronwyn Carlson and Terri Farrelly present settlers – whom historian Patrick Wolfe denoted ‘colonisers who never left’ – with a handbook on the failings of mythologised colonial history and the negative ramifications of this mythical history to this day. They argue that this history-telling is structurally intrinsic to many ideologies held by settlers since their fraught but recent history on this continent began. Over the course of ten comprehensive chapters Carlson and Farrelly describe the history behind colonial monuments and their relevance to a modern Australia.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Cole Baxter reviews 'Monumental Disruptions: Aboriginal people and colonial commemorations in so-called Australia' by Bronwyn Carlson and Terri Farrelly

- Book 1 Title: Monumental Disruptions

- Book 1 Subtitle: Aboriginal people and colonial commemorations in so-called Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Aboriginal Studies Press, $39.99 pb, 347 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

‘Commemorations are generally created and maintained by people with sufficient power to impose public consent to the existence of such commemorations,’ write Carlson and Farrelly. The power imbalance between settlers and Indigenous Australians is especially visible within the Eurocentric version of history that is forced onto our society. Checkpoints of invasion are often re-told through a one-sided settler’s lens, which gives a skewed depiction of what is truly a modern set of Australian values. History told and experienced by Indigenous Australians has often been left out of mainstream national holidays and commemorative statues.

As Carlson and Farrelly point out, modern Australian values have become more diverse and no longer solely emblematic of the ethos behind such structures as Invasion Day/Australia Day and the Hyde Park statue of James Cook. This indicates the desire for truth-telling now among some settlers in the twenty-first century. Atrocities of the past cannot be dealt with if so-called Australia insists on defining itself as egalitarian. Settlers ‘have a duty not to pretend it didn’t happen’, as Bruce Pascoe wrote in 2007.

It’s no wonder Pascoe is quoted in this book several times. Dark Emu, Pascoe’s seminal 2014 masterpiece, is essential reading for anyone wanting to understand what Australia was, and what it has the potential to be if we embrace the knowledge of the longest standing sophisticated culture in history. Carlson and Farrelly show that there exists many colonial barriers to the telling of historical truths by the government, mainstream media and white Australian culture. These often include push-back from any claims that don’t perfectly align with imperialist philosophy, such as the immense racism that Bruce Pascoe received in the wake of Dark Emu’s success.

As has become abundantly clear, there are infinitely more things that the ‘mythuments’, as Carlson and Farrelly refer to them, of so-called Australia don’t tell you. One damming fact is that many parts of this continent were visited by overseas societies before the first Pacific voyage of Lieutenant James Cook in 1768. 1606 saw the first documented European exploration of an Australian coastline by Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon, on the western side of Cape York peninsula, a landing that followed those of many Melanesian visitors trading with Indigenous people.

Six years from when it was first done, the ‘No pride in genocide’ graffiti spray-painted on the Hyde Park James Cook statue may more accurately sum up where present Australian values are headed than it did in 1770, when the explorer ‘discovered’ this territory that had already been known as Eora Country and occupied for tens of thousands of years.

Nonetheless, the myth of white permanence at the cost of black erasure is still pervasive on this continent, as was made apparent by recent news of Wiradjuri man and media personality Stan Grant having to step down from his position at ABC, due to racially motivated threats made against his family. Sadly, this is nothing new for Grant. He was also the subject of a public outcry in 2017 when he publicly spoke of the hypocrisy of the ‘discovered this territory 1770’ plaque at the Hyde Park James Cook statue. According to historian Mark McKenna, then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in effect argued that the ‘editing of statues and inscriptions was an attempt to deny; rewrite and even obliterate history, likening such moves to Stalinism’. In so-called Australia, a place that often claims to be progressive and gives a nod to reconciliation with Indigenous people, you might think an Indigenous newsperson would be able to describe what is wrong with the words on a statue.

This book is a highly valuable educational resource that represents many Aboriginal and progressive settler Australians views. It covers the fantasies of peaceful settlement, settler denialism, proud memorials to racism, and the flawed self-centralising Eurocentric version of written history since invasion. Through Carlson and Farrelly’s exhaustive research, the once fiction of peaceful relations between settlers and Indigenous Australians have a fair chance of becoming our shared future.

Comments powered by CComment