- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Chatterton syndrome

- Article Subtitle: An all-too-human story

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Nick Drake’s ‘Fruit Tree’, one of his best-known songs, addresses the idea that even if an artist is ignored in their lifetime, their legacy can be secured, and their work imortalised, with an early death. The song, as we learn from Richard Morton Jack’s exhaustive biography of the English singer-songwriter, was partly inspired by the precocious English boy poet Thomas Chatterton, who committed suicide at the age of seventeen, in 1770.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Barnaby Smith reviews 'Nick Drake: The life' by Richard Morton Jack

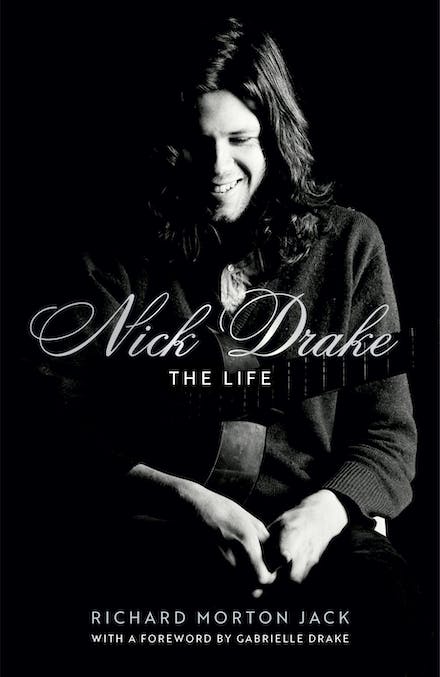

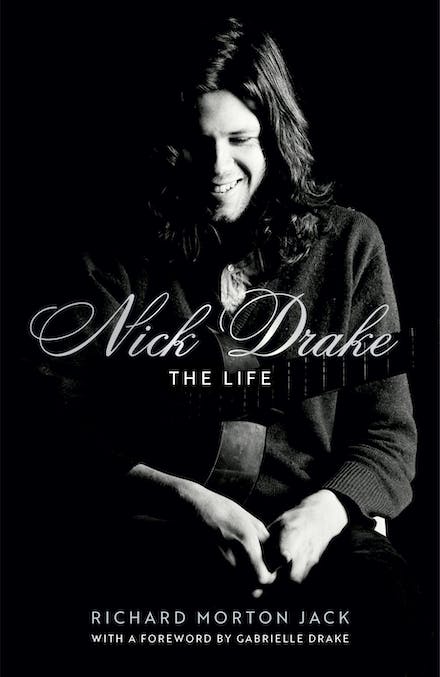

- Book 1 Title: Nick Drake

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $34.99 pb, 576 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Morton Jack narrates Drake’s life in forensic detail, straightforward prose, and at a rapid pace. Drake was born in 1948 in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), to British parents making their fortune in Asia during the last throes of empire. Upon his family’s return to the United Kingdom, he enjoyed a privileged childhood in rural Warwickshire, before attending the prestigious Marlborough College. Although nothing special academically, he went on to read English at Cambridge, but dropped out to focus on his music career in 1969.

Some of the period’s most respected musical names were involved in the creation of his three albums, drawn to songs defined by astonishing acoustic guitar picking, experimental tunings, and cryptic but vivid lyrics. These included producer Joe Boyd, guitarist Richard Thompson, stand-up bass player Danny Thompson, and founding member of the Velvet Underground John Cale, to name a few. Despite this, his albums did not sell and his profile remained low – partly because of his aversion to performing live and promotion. After the unsettlingly sparse Pink Moon album (1972), Drake’s life became a saga of mental illness as he spiralled downwards due to an unspecified condition – or combination of conditions, depression likely being one – about which Morton Jack is careful not to draw definitive conclusions.

Morton Jack has stated in interviews that he wished to quash certain myths about Drake. One of these is that he was an out-of-control smoker of marijuana or a consumer of stronger drugs; the book becomes rather repetitive in repudiating this. Morton Jack also frequently asserts that Drake, who appears to have never had a close romantic relationship of any kind, was not gay or bisexual.

There is a more important misconception about Drake that The life deals with well: the notion that his slide into depression was in response to the perceived failure of his music career. Such an idea is almost offensive in its misunderstanding of the complexity and depth of his psychological problems. After describing a stay in hospital due to kidney stones, Morton Jack writes: ‘The alarming fact appeared to be that whatever Nick was grappling with did not have an immediate cause, either in his kidneys or his career; it ran deeper.’ The last quarter of the book details erratic and disturbing behaviour, including violent outbursts. Several of the medical professionals seen by Drake suggested that he had schizophrenia, though Morton Jack seems unconvinced. In addition, some of Drake’s behaviour, even in his earlier ‘healthy’ years, exhibited many signs consistent with autism. The core of his mental health problems did not stem from environmental factors (even if he reacted to an array of triggers).

Drake’s music has inspired some wonderful writing over the years, particularly the essay ‘Exiled From Heaven: The Unheard Message of Nick Drake’ by music critic Ian Macdonald (available in Macdonald’s 2003 book The People’s Music) and a dazzling chapter titled ‘Orpheus in the Undergrowth’ by Rob Young as part of his wider tome on English folk-influenced pop music, Electric Eden (2010). These offer literary analysis of Drake’s music and poetics, something not prioritised in The life. Instead this is a tenaciously researched, highly disciplined and objective piecing together of the what, where, and when of Drake’s short life, and is unimpeachable on those terms. With this definitive biography finally in the world, his songs now deserve further scholarly attention and criticism (in the vein of, say, Christopher Ricks on Bob Dylan).

Chatterton’s posthumous fame was partly fuelled by the famous 1856 painting The Death of Chatterton by the Pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis. It depicts the lifeless poet sprawled on a bed after drinking arsenic. Nick Drake was similarly sprawled across his bed when his mother Molly discovered his body after he overdosed on anti-depressants. That painting reinforced the image of Chatterton as doomed Romantic hero, more myth than man. Nick Drake: The life goes a long way to ensuring its subject is not similarly distorted and will be remembered as an all-too-human figure, albeit an extraordinarily talented one.

Comments powered by CComment