- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Men, money and the military

- Article Subtitle: Time for a human revolution

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

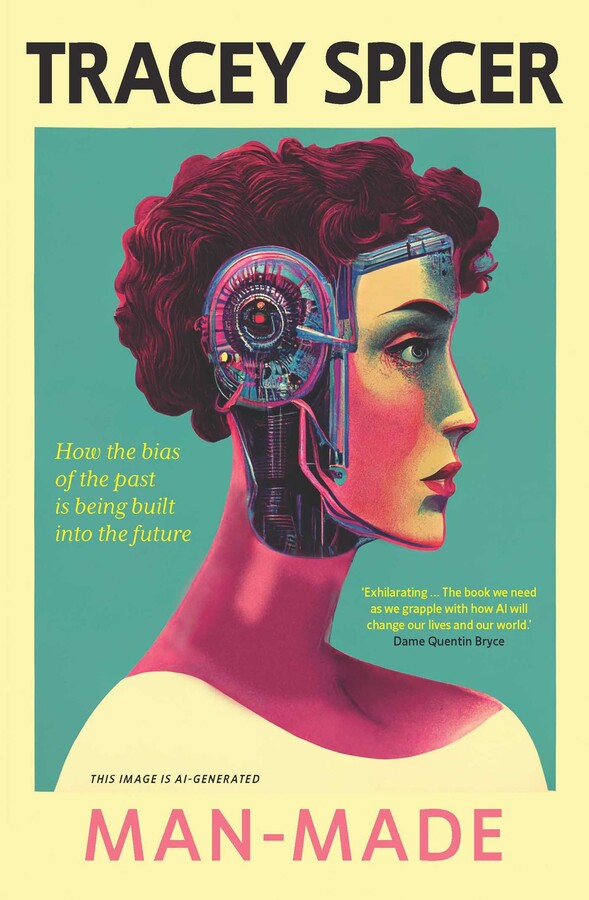

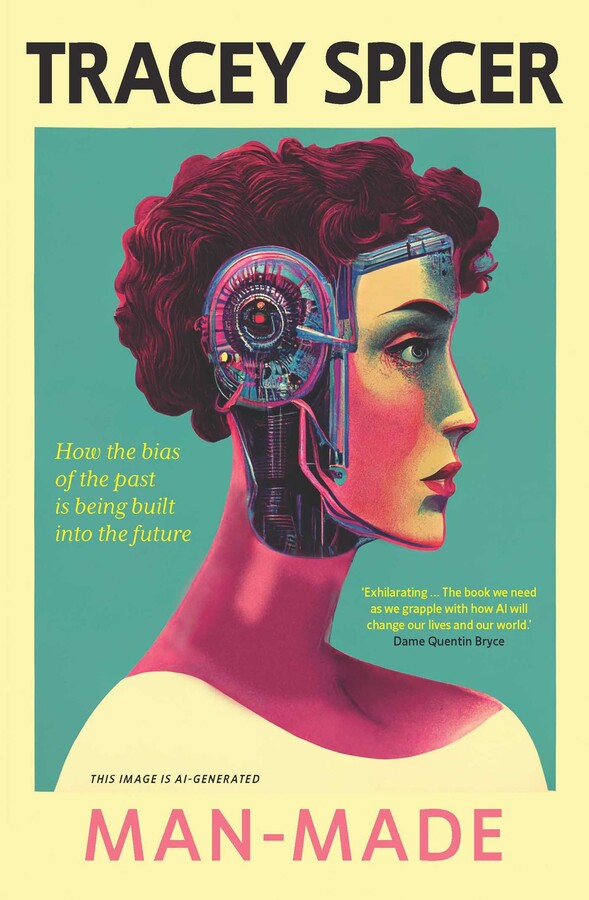

Man-Made: How the bias of the past is being built into the future recounts findings from a six-year ‘mission’ to ‘identify the villains’ in the world of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Uncovering the history and future of AI through a feminist lens, Tracey Spicer puts the conservatism at the heart of these oft-touted ‘revolutionary technologies’ on full display. Spicer contextualises AI’s current omnipresence in a world ruled by money, the military, and men. Interlacing an impressive range of vignettes, Man-Made introduces the reader to everything from AI’s origins in women’s weaving, to racist soap dispensers, to Sexbots, to gaming, to driverless cars, to childcare robots, to the end of humanity.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ruby O'Connor reviews 'Man-Made: How the bias of the past is being built into the future' by Tracey Spicer

- Book 1 Title: Man-Made

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the bias of the past is being built into the future

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $34.99 pb, 291 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In an unsurprising twist, women’s contributions to AI, and technology in general, have more often than not been undermined or obscured. Women in important roles were referred to in bulk by fun feminine nicknames like the ‘ENIAC girls’ (for the women who worked on the world’s first general computer during World War II) or ‘LOL [Little Old Ladies]’ (the women who worked at NASA to send Apollo to the moon). Man-Made also delves into how women are under-represented or missing from key datasets used to train algorithms – resulting in ineffective or dangerous AI tools. They are absent, too, from decisions about how these tools should be used. As Spicer puts it, AI tools are ‘designed by men, for men’.

There has always been an apocalyptic side to discussions about AI. Governments, ‘AI experts’, and companies alike proclaim AI as our saviour – here to free us from the poverty and environmental catastrophes of our own making. In the same breath, they warn that AI could spell our destruction. Even the Elon Musks of our world proclaim that AI is our ‘biggest existential threat’ and are aghast at the lack of government regulation. Still, they soldier on, continuing to produce their own AI products and raking in enormous profits. Spicer herself declares AI could be ‘one of the greatest threats to the continuation of the human race’. Yet, the many anecdotes and conversations Spicer provides chronicle more familiar threats and abuses, suffered due to bias, thoughtless design, and targeted use. The chapter on coercive control, for instance, illustrates how technology is already an everyday nightmare for many women and other victims of domestic abuse. In these scenarios, technology enables perpetrators to control their partners and ex-partners from a distance – tracking their movements and haunting their houses. But this reality doesn’t call for a sexy spaceship to Mars (à la Musk or Bezos), and the monsters in these stories are typically men, not machines.

In other everyday horrors, police use of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) has resulted in numerous wrongful arrests. The technology, often trained on white, male faces, has difficulty telling non-white, non-male faces apart. Black men going about their daily business have been a particular target across the United States. Then there are the cases of technology being used on vulnerable populations in the form of welfare control. Australian readers will recall the recent ‘Robodebt scandal’.

Despite governments knowing about many of these issues, they are awfully slow to regulate AI or the companies producing it. The European Union is currently debating wide-ranging AI legislation under a proposed AI Act – a world-first, though many activists argue that it doesn’t go far enough to protect vulnerable people. Other countries, Australia included, are entirely reliant on voluntary ethics frameworks.

Spicer concludes that this hesitation may have to do with the big ‘P’ – not patriarchy this time but profits. It seems that governments are just as taken as companies with the notion AI might generate unlimited wealth for those who develop and use it first. It’s a zero-sum game as any good capitalist knows. Yet this obsession with ‘moving fast and breaking things’, just to get somewhere ‘first’, has hugely damaging consequences. For now, humans rather than robots are the ones continuing to wreak havoc.

Spicer’s suggestions for how we might change course are reminiscent of those that accompany books like Data Feminism by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein (2020), or Future Histories by Lizzie O’Shea (2020). Recommendations include having more diversity on AI design teams; asking questions of those who are building or using AI for commercial or political means, and demanding legislative reform and regulation. While this ‘call to action’ may not, in itself, ‘shake the tech sector to its foundations’, as the book jacket charmingly proposes, good advice bears repeating. Man-Made is certainly convincing. We really should address the myriad of problems Spicer identifies before the AI revolution devolves any further – or the robots kill us all.

Comments powered by CComment