- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay

- Custom Article Title: ‘Come closer and listen’: A tribute to Charles Simic (1938-2023)

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Come closer and listen’

- Article Subtitle: A tribute to Charles Simic (1938–2023)

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It took me years to gather enough courage to introduce myself. Finally, deep into the Covid lockdown and a few months after receiving an award for my first collection of poems, I began my correspondence with Charles Simic by sending him an email to share the news, as if he were a family member, the one who would understand. He replied warmly, kindly, and in Serbian: ‘Draga Jelena …’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ''Come Closer and Listen': A tribute to Charles Simic (1938-2023)', by Jelena Dinić

‘I was born – I don’t know the hour – slapped on the ass /And handed over crying / To someone many years dead / In a country no longer on a map,’ Simic writes in ‘Come Closer and Listen’, the titular poem in his penultimate collection. It is an autobiographical summation of his life journey, in his ninth decade – an invitation to the poet’s late musings. Simic’s Serbian roots and American perspectives collide at the cultural and literary intersection of two worlds. It is from this collision that the poet emerged to create his own voice.

Published in 2019, before the Covid pandemic and social distancing, Come Closer and Listen contains plenty of darkness – ‘There is also a cow / Whose eyes the soldiers took’ – yet it is imbued with Simic’s characteristic generosity, charm, and playfulness, sorely needed in a world that was about to face unprecedented change.

I discovered Simic’s writing by chance, when I was searching for my own poetic voice, in a foreign country, in a foreign language. I read him first as an American poet full of joy and jazz, until I was abruptly transported to the intimacy of a tiny kitchen in a Belgrade apartment. On one of his visits to Belgrade, Simic relates a story of breaking an apartment window with a ball just before he fled the city. It was still broken when he returned decades later. This echo of his childhood in long-lost Yugoslavia reminded me of mine, and it seemed that not much had changed between the wars that have defined the region. His distinctive voice forced me to consider my own. His minimalism slid off the tongue like silk, yet I felt its truth, like a knot in my throat. We were both born in a country that doesn’t exist anymore.

Simic left Yugoslavia with his mother in 1953. They spent a year in Paris before joining his father in Chicago. By then he was already reciting and reading poetry; this was not unusual for him, nor for his school friends in Belgrade.

Postwar, poetry was an important part of Yugoslavian existence. It reflected the ideology of communism, the fight for freedom, and the magical landscape of our country, from the river Vardar to the highest mountain of Triglav. Poets of the time were members of the Communist Party, although often under suspicion. Vasko Popa, Yugoslavia’s most translated poet, best known for his elliptical minimalism, had a profound influence on Simic. In Popa’s Games cycle of poems, a masterpiece of modern poetry, the fun is satiric, and the games are played according to new, dark rules. ‘Hide and Seek’ is a striking example: ‘Someone hides from someone else / Hides under his tongue / The other looks for him under the earth.’

We learnt the rules early. From Year One, we recited poetry about violets as a metaphor for our Leader. I wore a red scarf and a blue partisan cap, and gave my word of honour at a ceremony in the town’s theatre: to be a good comrade, a diligent student, a respectful daughter, and that I would look after our brotherhood and fight for our freedom. I still remember the sound of applause and a smile on my teacher’s face as I searched out my parents, hidden in the darkness of the last row.

My grandmother often told me, ‘Only if you know your poets can you know your country and your people.’ I read and reread the poets in her bookshelf, especially Popa. Although rooted in the Serbian folk tradition, his work represented a new poetic movement which expanded the boundaries of poetry and offered a tougher perspective on the postwar world. Simic, as a young poet, met Popa, whose poems he translated masterfully over several decades. He also wrote his own ‘Hide and Seek’ poem.

I have attempted to write my own version of the game. It is inherent to Serbia’s landscape, and those who look to find themselves or others, usually in the twists and turns of the political reality.

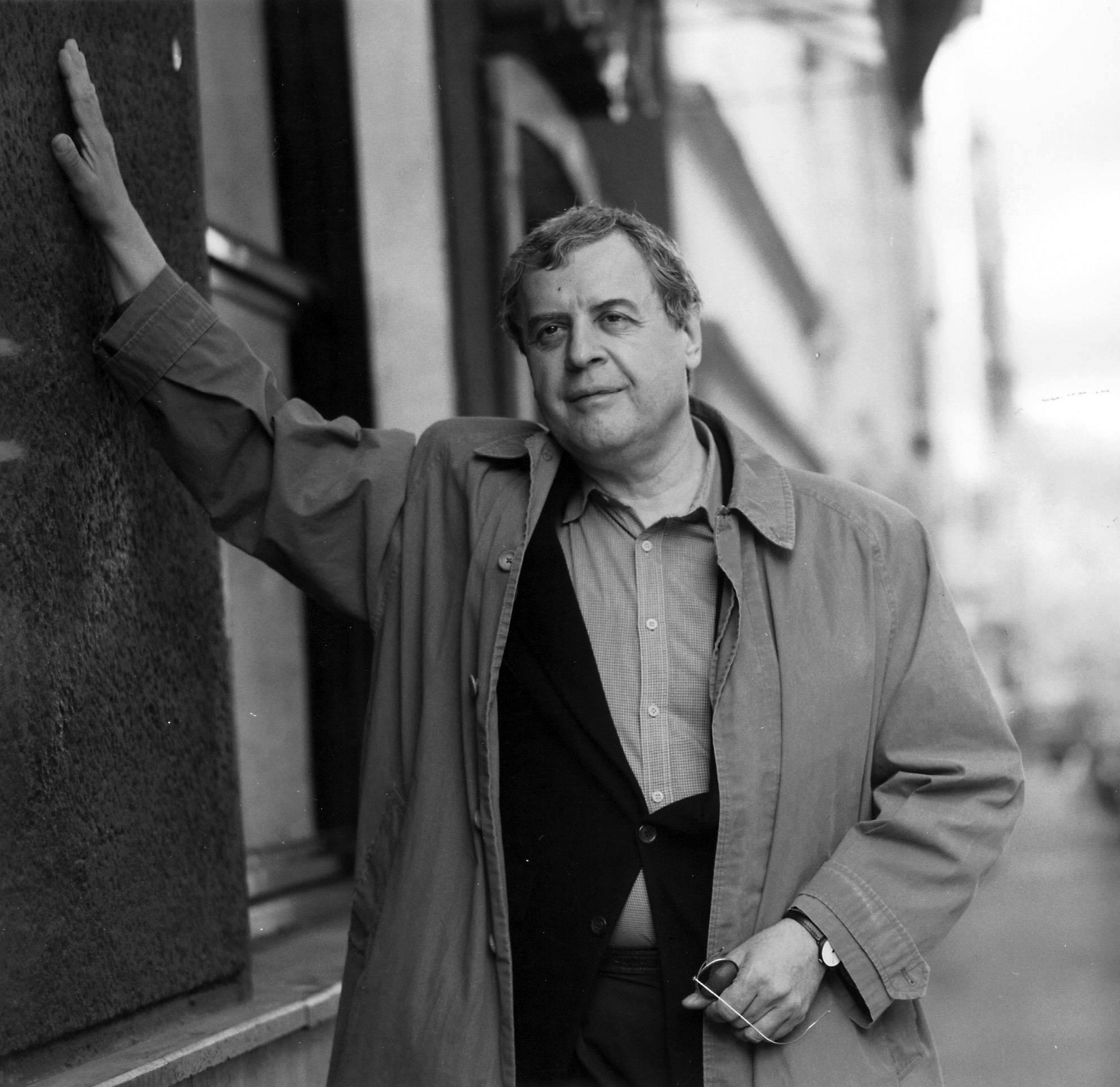

Charles Simic, 1994 (Brigitte Friedrich/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy)

Charles Simic, 1994 (Brigitte Friedrich/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy)

The strength of Serbian literary giants usually lies in their ability to draw on the rich oral tradition of the region. This tradition has provided a wealth of inspiration and material for writers, enabling them to create works of beauty, depth, and complexity. Its roots are in the epic folk poems that commemorate the struggle against the Ottoman Empire over many hundreds of years. It is a common practice for Serbian parents to name their children from this largely oral tradition. For instance, if it’s a boy, he must be as smart and strong as Dusan the Mighty, emperor of Serbia from 1331.

Simic’s appreciation of Serbian folk and epic poetry, and his mastery of the language, qualified him as translator of folk poems that had been sung and retold for generations. Initially collected and published between the eighteenth and nineteenth century by Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic, the reformer of the Cyrillic and Serbian language, these folk poems opened the door for Serbia into the European literary scene and were translated into English, German, Russian, and Polish.

Goethe compared the Slavic folk ballad ‘Hasanaginica’ (‘Song of the lament of Noble Wife of Hasan Aga’) to the ‘Song of Songs’ and translated it into German in 1775. He famously asked: ‘Who are those Serbs and what is their culture like?’

With the civil war raging and Yugoslavia collapsing, I arrived in Australia with my sister and parents in November 1993. There is a grey photograph of us wearing home-knitted jumpers, looking displaced at Sydney airport. A few volumes of poetry felt heavy in my suitcase. Their memorised lines became an even greater burden as I unpacked into homesickness. Deeply unsettled, I returned alone to my home in the still war-torn country a year later.

Simic, on the other side of the world, was putting the country together again in the form of an anthology, by translating Yugoslav poets, including folk poetry. He called the anthology The Horse Has Six Legs (1992) and shared its beauty with the world. It earned him the Harold Morton Landon Translation Award. In her citation, award judge Carolyn Kizer wrote, ‘The ironies, in 1993, of giving an award to Serbian poets will be evident to many, but the glory of great poetry is that it transcends its time and these agonized events to enter the universal realm of art.’

One of Simic’s reviewers observed that in Serbia everyone is a lover of poetry, even war criminals. (The notorious Radovan Karadzic was a poet himself.) In the 2010 introduction to the updated edition of The Horse Has Six Legs, Simic noted, ‘Everyone knew the names of Serbian war criminals, but almost no one knew the names of its writers and poets.’

Simic was professor emeritus at the University of New Hampshire since 1973, recipient of major literary awards, and poet laureate of the United States. His contribution to poetry and literature, English and Serbian, will be remembered and celebrated for years to come.

I hold Come Closer and Listen as a gift. A few of his encouraging words for my own writing made me smile for days. An unsent email still haunts me. In a recent dream, I was walking in Adelaide’s Garden of Unearthly Delights carrying a love poem that I showed to everyone. It was magical, and in English. Then I realised it had no ending and woke up. The magic was gone. I was left wondering: what happened in the end? Or, does it matter if we lovers are together? Come Closer and Listen quietly ends with the poem ‘Last Picnic’: ‘If it gets cold – and it will – I’ll hold you close. / Night will come early. We’ll study the sky hoping for a full moon / to light our way /And if there isn’t one, we’ll put all our trust in your book of matches / And my sense of direction / as we go looking for home.’

Comments powered by CComment