- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Two books about the dangers of deception

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Of spies and lies

- Article Subtitle: Two books about the dangers of deception

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The life of a spy is based on lies, but both these books make an attempt to separate fact from fiction in the stories of their subjects.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Sexton reviews two books on Australian espionage

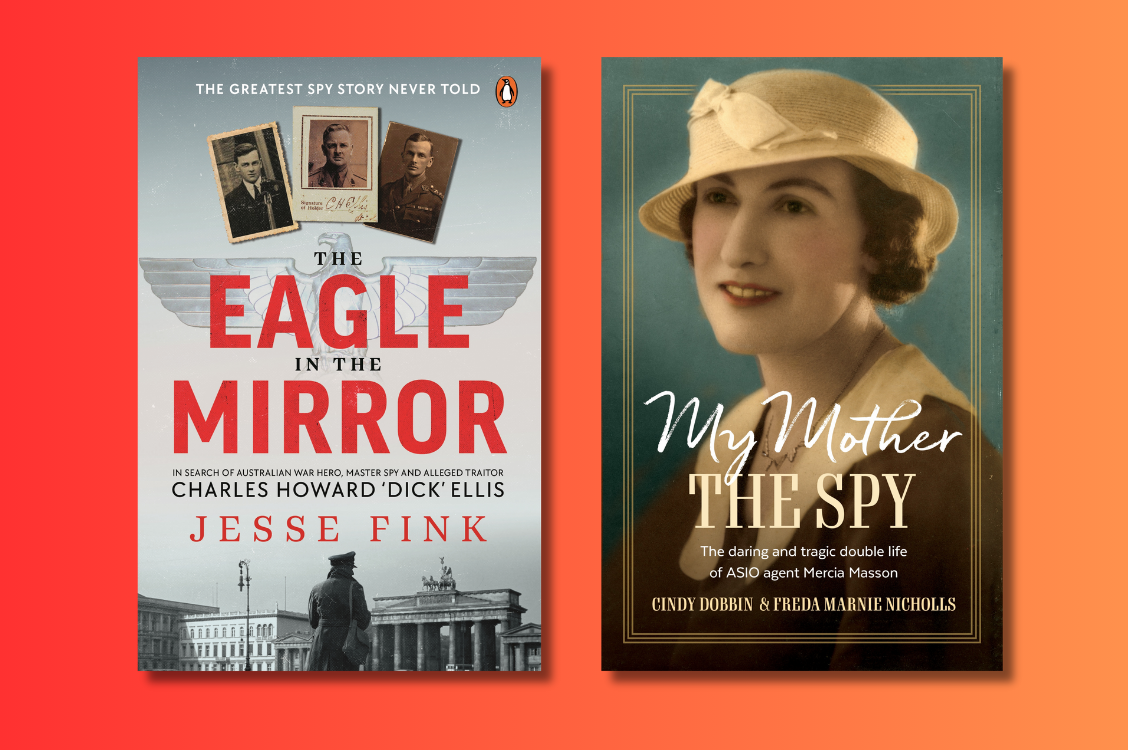

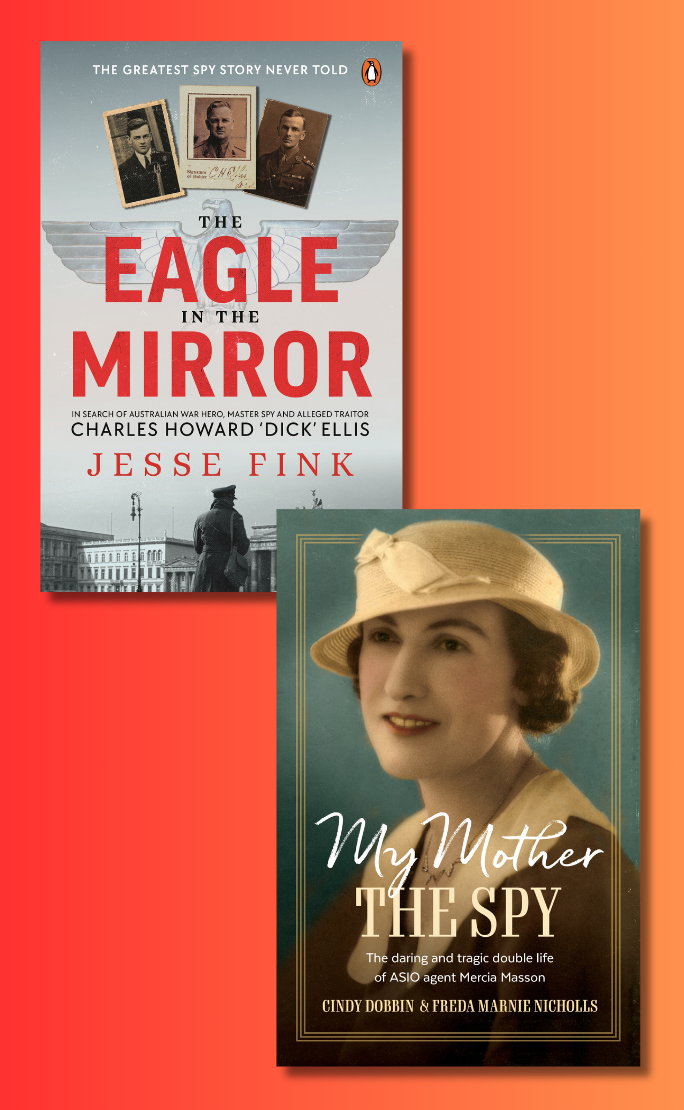

- Book 1 Title: The Eagle in the Mirror

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

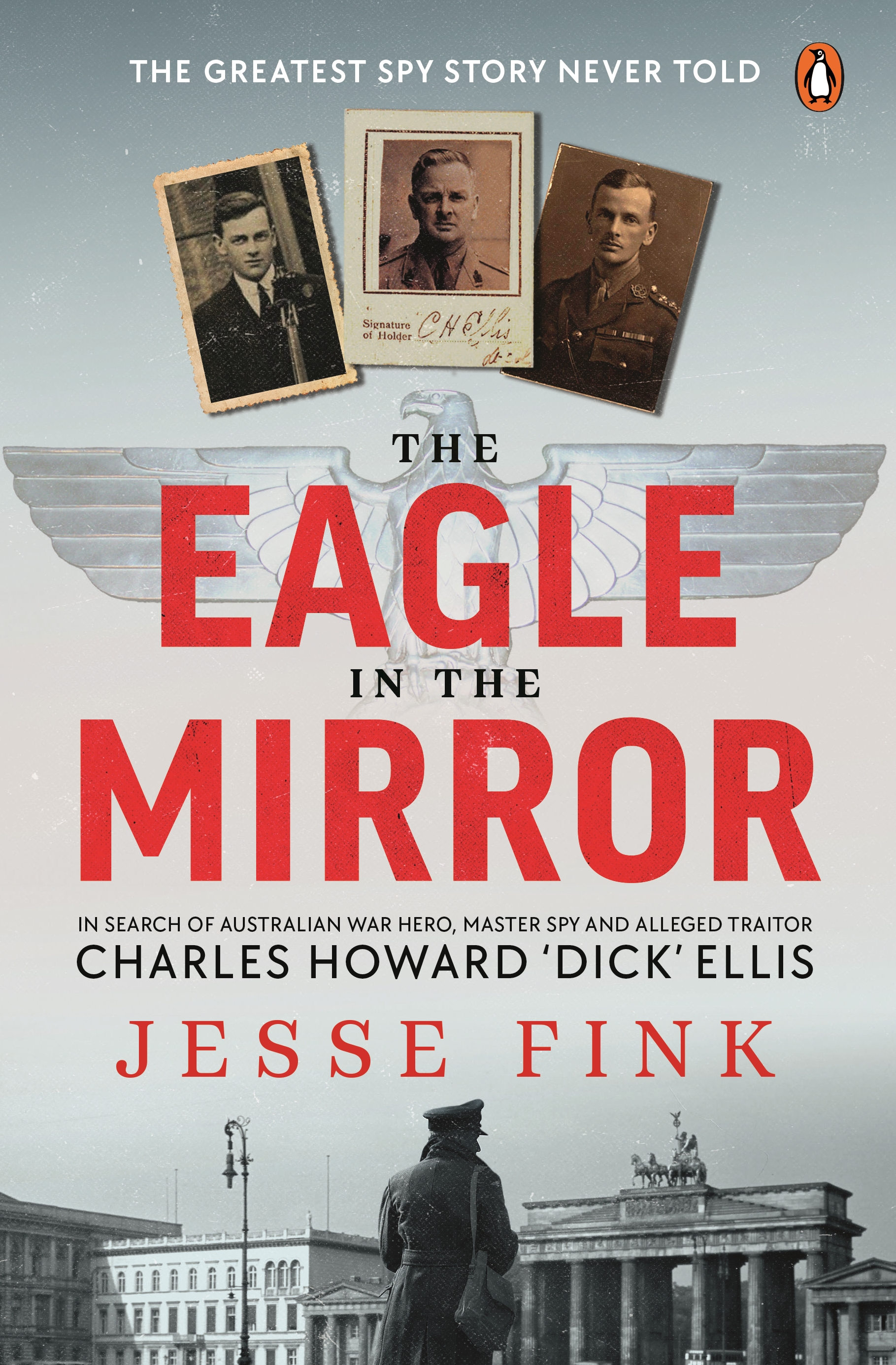

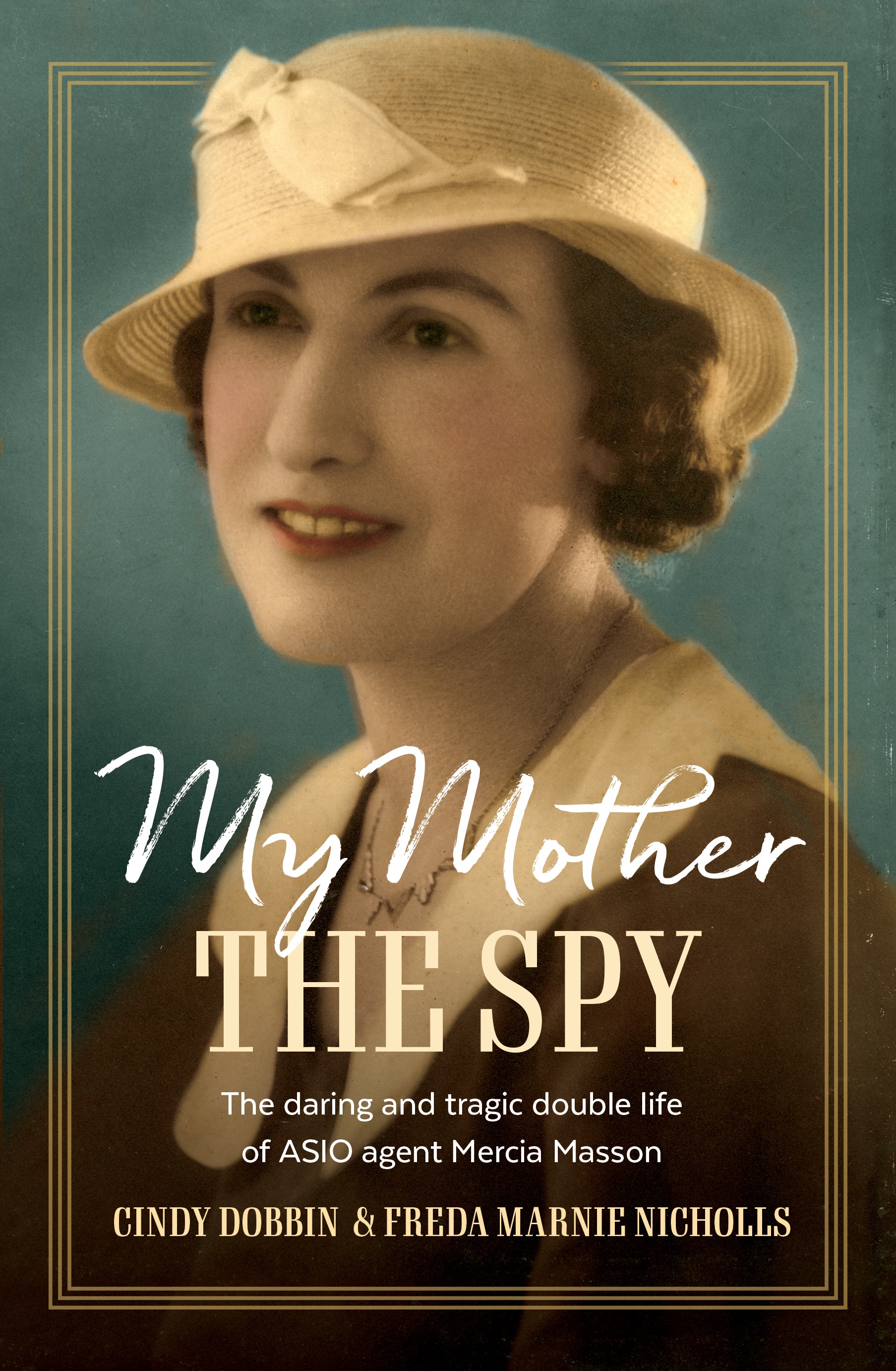

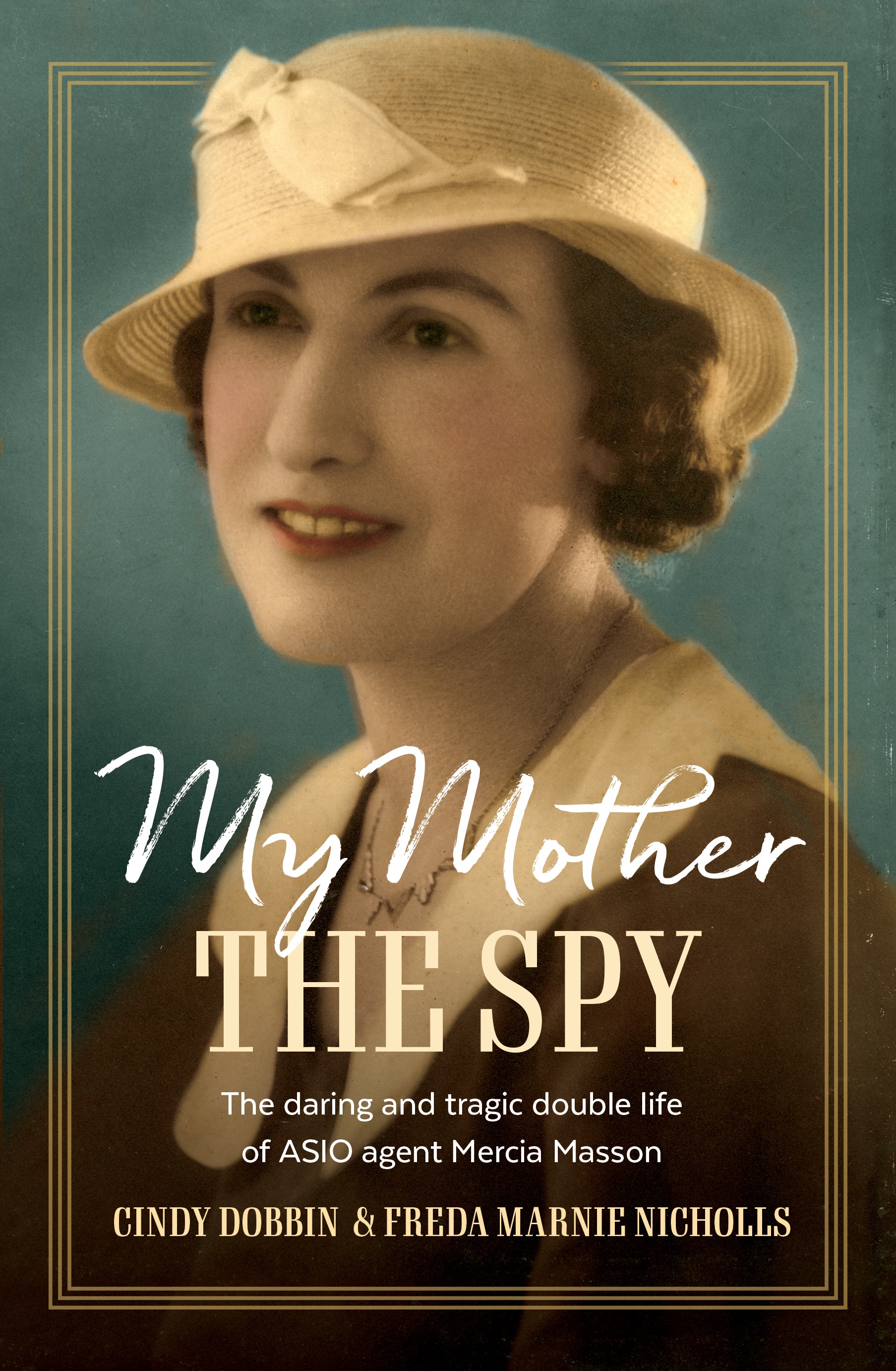

- Book 2 Title: My Mother the Spy

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 320pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the decade after the war, Ellis moved to the same kind of work in the Foreign Office and then, after Russian language training at Oxford University, to MI6, with postings to Constantinople, Berlin, and Geneva. Sometimes his real role was disguised as a member of British Embassy staff in these places, but more often he was nominally employed as a foreign correspondent for the Morning Post newspaper. After spending most of the 1930s in London, he went in 1940 to New York, now with the rank of colonel, to be second in charge of the British intelligence presence in the United States, where he helped set up the Office of Strategic Services, later converted into the CIA. In 1944, he returned to the United Kingdom and was put in charge of operations for the Far East and the Americas. Six years later, he was in Canberra to advise on the operations of the newly formed ASIO. After alternating for some years between England and Australia, he retired to the United Kingdom in 1957 but was soon back with MI6.

In the mid-1960s, Ellis was interrogated at length inside MI6 about allegations that he had provided information to the Germans in the 1930s and to the Soviets in the years after the war. None of this was public at the time, and Ellis died in 1975, but in 1981 the British journalist Chapman Pincher published an explosive book, Their Trade is Treachery, alleging that Sir Roger Hollis, a former head of sister agency MI5, had been a Soviet agent and that Ellis had been a triple agent. These charges were reiterated in Spycatcher (1987), by Peter Wright, who had been Pincher’s chief source and one of Ellis’s interrogators. Spycatcher was the source of litigation in Australia when the British government unsuccessfully attempted to prevent its publication here after successfully doing so in Britain.

Ellis's defaced student portrait, Oxford University, 1921. The notation in Russian reads 'Anarchist' (National Library of Australia, from The Eagle in the Mirror)

Ellis's defaced student portrait, Oxford University, 1921. The notation in Russian reads 'Anarchist' (National Library of Australia, from The Eagle in the Mirror)

It is not always easy to track these confusing events through the book, which really needed a good editor, but the author, who is a strong defender of Ellis, concludes that there is no real evidence to support the theory of his having been a Soviet agent. As to the provision of information to the Germans in the 1930s, it may be that Ellis admitted to this, and it may also be that it was done, if at all, on orders from superiors who wanted to maintain contact with German intelligence. It must be remembered that in the 1950s and the 1960s Western intelligence agencies were obsessed with the notion of the mole who had infiltrated their ranks and supplied all their secrets to the Soviets. There were, of course, moles – Kim Philby at MI6 was the most famous of them. Often these mole hunts took over the whole organisation and paralysed its operations. If this book tells us anything, it is the difficulty of knowing the truth of anything in the world of the security services.

As already noted, Ellis had an involvement with ASIO in its early days. It is this organisation that is at the heart of the story of Mercia Masson, as told by Freda Marnie Nicholls with the assistance of Masson’s daughter, Cindy Dobbin. Masson was born in Sydney in 1913 and worked as a journalist in Melbourne and Newcastle in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It was while working for the Daily Telegraph in Sydney in 1945 that she began to act as a source for naval intelligence and then for the Commonwealth Investigation Service. She moved between the Commonwealth bureaucracy and journalism while still carrying out this double role, albeit seemingly without payment. She was picked up as an informant by ASIO soon after its establishment in 1949. ASIO did provide some financial support to Masson, but its extent is unclear.

At this time, ASIO was largely concerned with the Australian Communist Party and its front organisations. Until the election of the Whitlam government in 1972, ASIO saw nearly all threats to national security as coming from left-wing organisations and individuals, including innocuous opponents of the Vietnam War in the 1960s. But in the immediate postwar years, Communist Party members were loyal only to the Soviet Union and, as the book makes clear, were prepared to spy for it if able to obtain access to classified information.

One of Masson’s communist contacts was a journalist with the party’s newspaper Tribune, Rex Chiplin, who was a member of the Canberra press gallery. Masson and Chiplin confronted each other at the Royal Commission established in 1954 to consider Soviet espionage activity in Australia in the light of the defection of Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrov. Although her evidence was to be given in secret session, Masson did not want to appear before the Commission, but it insisted. The public was duly excluded, yet Chiplin was present as a subject of the Commission’s interest. He was no doubt astonished when Masson’s double role was revealed. He retaliated by suggesting that she had given him classified material when working in one of her public service positions, although the Commission rejected this as untrue.

Mercia Masson at Kilcare (from My Mother the Spy)

Mercia Masson at Kilcare (from My Mother the Spy)

Chiplin may have had the last word. In an article in the British Guardian in December 1955, Masson was named as an ASIO agent and described as a ‘florid, gushing, gossipy, neurotic woman’ who was ‘loyal to nobody’. The article was then reprinted in Tribune. Even before this publication, however, her evidence before the Commission had been made public and, although her name was not used, her identity would have been clear to quite a number of her friends and acquaintances.

Over the next twenty years, until her death in 1975, Masson went back to journalism, largely with the ABC, and became involved in the arts world in Sydney. Sometime after her death, her daughter discovered that ASIO had paid for her mother’s funeral, showing some loyalty to its former agent in this final gesture.

Both these books demonstrate that in a world based on lies, however necessary they may be in the national interest, there are just as many dangers for spies as there are for the victims of their deception.

Comments powered by CComment