- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Capturing the mood

- Article Subtitle: A new addition to a tricky genre

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

'State-of-the-nation’ books are a tricky genre: for every The Lucky Country (1964), Donald Horne’s bestselling indictment of 1960s Australia, there must be at least a dozen more which fall swiftly into obsolescence. Yet this common fate is not necessarily a bad thing: such books are meant to be timely, not timeless. As an intervention into the contemporary moment, such texts’ success or value resides in fresh and useful analysis which is currently lacking elsewhere; and the ability of the author to capture a mood that is, if not ‘national’, at least pervasive enough to be widely recognisable. At the same time, it helps if that mood has not yet been properly articulated. To raise the bar further, the best of them offer both vital historical perspective and a path forward, and are written in a persuasive and accessible style which stops short of polemic but resists hesitant equivocation.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Zora Simic reviews 'The Shrinking Nation: How we got here and what can be done about it' by Graeme Turner

- Book 1 Title: The Shrinking Nation

- Book 1 Subtitle: How we got here and what can be done about it

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $32.99 pb, 232 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

On the basis of the generic criteria sketched above, Graeme Turner’s latest (and approximately thirtieth) book, The Shrinking Nation: How we got here and what can be done about it, hits its marks. His argument that the nation has shrunk – ‘that it is now less than it was, and less than it should be’ – is compelling, especially as he begins with the ‘dysfunctional state of Australian political culture’. The features he identifies – rotating leaders, most of them ‘professional politicians’ devoid of vision beyond political survival; systemic corruption with a corresponding lack of accountability; and the punitive cruelty of bipartisan border policies, to name just a few – are so entrenched that most readers will find a catalogue of them depressing and familiar reading. Still, it is a necessary starting point for a wider discussion of the corrosive effects of rolling cultural wars and economic rationalism, or more broadly neoliberalism, on public life and its key institutions, including the public service, universities, and the media.

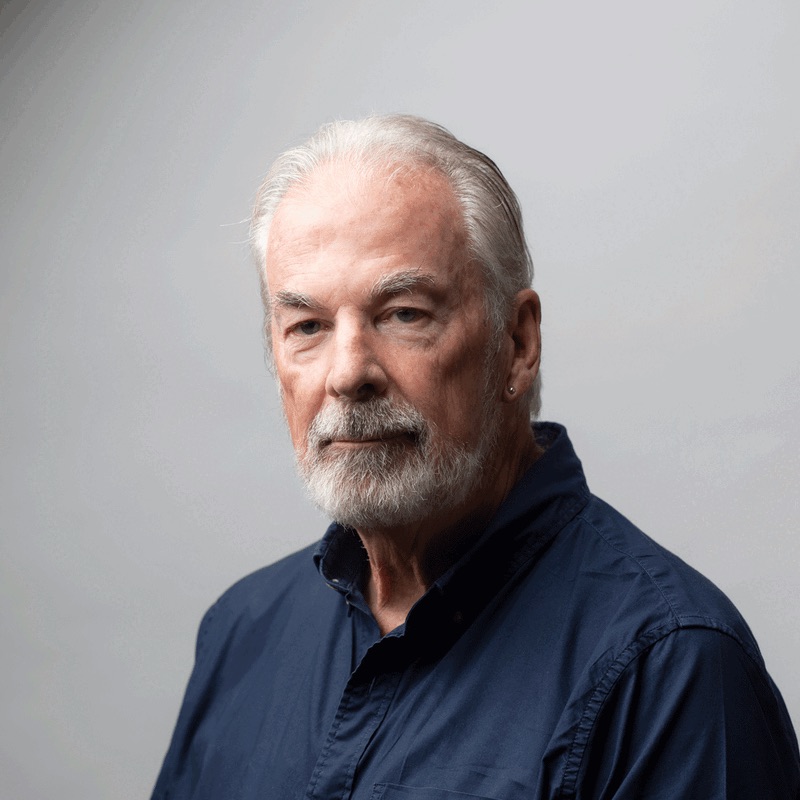

Graeme Turner (photograph by Russel Shakespeare courtesy of University of Queensland Press)

Graeme Turner (photograph by Russel Shakespeare courtesy of University of Queensland Press)

An adept synthesiser and generous scholar, Turner navigates the terrain with due recognition of the contributions of others, from well-known political and economic commentators such as Laura Tingle, Bernard Keane, Sean Kelly, Ross Gittins, Richard Denniss, and George Megalogenis (currently Australia’s most prolific and consistently insightful ‘state-of-the-nation’ writer) through to academic experts such as Harvard historians Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, authors of How Democracies Die (2018), and fellow cultural and media studies scholars, including Mark Andrejevic, author of Automated Media (2019).

Turner does not always entirely concur with those he cites (when it comes to the pros and cons of social media, for instance, he veers towards the pessimistic camp), but he does model a respect for knowledge and expertise which he argues has been devalued by mainstream politics and media. In making this case, Turner acknowledges US writer Tom Nichols’s book The Death of Expertise: The campaign against established knowledge and why it matters (2017), while pointing out what is distinctive about Australia. Here, the ‘public engagement of academics’ has ‘shrunk significantly over time’, a development that Turner explains is at least partly due to the ‘manner in which the politicians and the media have treated them’ and ‘Australia’s residual anti-intellectualism – which is always there to be revived, even when apparently dormant, in the service of political interests’.

Throughout, Turner draws on his own past research. It is at these points that The Shrinking Nation begins to transcend the limits of the ‘state-of-the-nation’ genre. As a long-time observer of, and participant in, ‘national’ culture (variously defined, including by him), Turner – an inaugurating and hugely influential figure in cultural studies and its offshoots in Australia – is uniquely and generatively placed to explain ‘how we got here’ and to defend a positive sense of the ‘nation’ against its more insidious and divisive variants. Harking back to one of his best-known books, Making it National: Nationalism and Australian popular culture (1994), Turner notes ‘the many warning signs’ that prefaced our contemporary moment, including how high-profile businessmen like Alan Bond and John Elliott harnessed the cultural nationalism of the time for their own profitable interests. Elsewhere, Turner laments what he sees as the dismal state of ‘legacy media’, such as television news and current affairs, with reference to his book Ending the Affair: The decline of television current affairs in Australia (2005).

Ever alert to the contradictory effects of social and cultural change, and keenly aware that ‘the project of nation formation has gradually moved into background of most western democracies’, Turner carefully argues for its updated continuation and for the benefits of Benedict Anderson’s now unfashionable concept of an ‘imagined community’. On this front, he is most convincing when offering specific suggestions, as he does when citing his recent collaborative research on shifts in Australian cultural policy to argue for an updated version of the Keating government’s Creative Nation policy statement of 1994.

When surveying the contemporary cultural landscape for positive signs of national culture or renewal, however, Turner is on shakier ground – not because there are no examples (he provides plenty), but because he missed opportunities to offer nuance or closer analysis at crucial points. Public mourning over the death of cricketer Shane Warne, for example, is uncritically elevated to a ‘national celebration’ which delivered ‘the pleasures of belonging’. And while sensitive to the enduring racism and sexism of dominant national imaginaries, Turner approvingly notes the ‘heightened visibility’ of ‘young, Indigenous women in public debate’ without naming any of them, or engaging with their ideas. Then again, if he had foregrounded Chelsea Watego’s Another Day in the Colony (2021) or any number of challenges to ‘so-called Australia’ from First Nations writers, the notion of a ‘people’s nation’ would be harder to envision and defend.

State-of-the-nation books can capture the Zeitgeist, but always run the risk of being outrun by history itself. As a new addition to the genre, The Shrinking Nation is thoughtful, well-informed and sometimes rousing, elegantly written by a cultural historian who has long valued publicly engaged scholarship. While some aspects are already inevitably dated (the notion of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament has become much more divisive), much of what Turner describes is still playing out, and will do so for some time. But even as Turner impressively meets the state-of-the-nation brief, he also leaves the ‘we’ to whom his assessment is addressed unexamined. With the proliferation of alternative perspectives on Australia, from the writings of Behrouz Boochani to the edited collections of Sweatshop – developments Turner does not canvass – the limits of the genre have arguably never been more apparent.

Comments powered by CComment