- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Girl and Sylvia

- Article Subtitle: An invigorating work of many faces

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

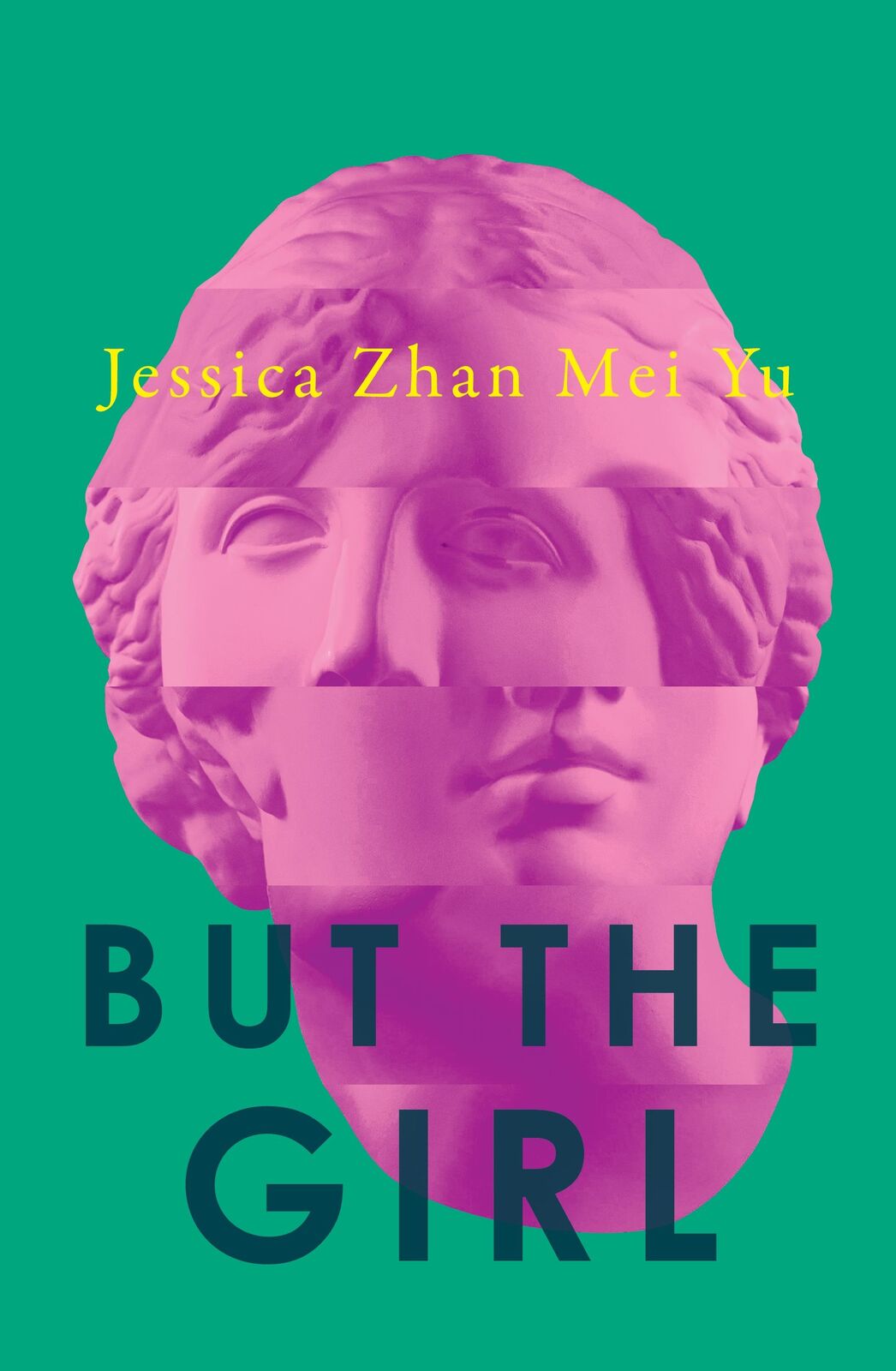

In the modern literary landscape, the novel about a novelist writing a novel has become de rigueur. It can provide an ideal setting for a meditation on the complexities of living a creative life. Jessica Zhan Mei Yu’s début novel, But the Girl, follows in this contemporary tradition, but offers something more compelling than navel-gazing: a critique of classical literature, specifically the work of Sylvia Plath, through personal and academic lenses.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen reviews 'But the Girl' by Jessica Zhan Mei Yu

- Book 1 Title: But the Girl

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Girl’s inner monologue speaks to the common experience of internalised racism and misogyny: ‘I felt instinctively that while on the outside I was always going to be “Asian”, on the inside I was the brown-haired girl whose clothes spoke of a woman with a conspicuous and interesting inner life.’ When Girl is a high-school student, a male teacher who teaches but dislikes Plath takes a liking to her. She suppresses her growing fascination with the poet to parrot his opinions and gain his approval; when she summons the courage to offer her own vastly different interpretation, the approval is immediately revoked. It is an early example of a power struggle that plays out further in the academic setting and throughout within the family unit; much of the novel concerns Girl’s learning to reclaim interpersonal and intellectual space.

The thorny implications of race within institutional and personal relationships have been examined in recent Australian literature, such as Jessie Tu’s A Lonely Girl is a Dangerous Thing (2020). That novel and this one both interrogate expectations and impacts of filial piety and family sacrifice within the structure of a Künstlerroman.

Domestic and family life and history are an important element of the novel and wind throughout; Girl’s knotty family relationships are the first basis for her personhood, as important as the literature she later discovers. Her novel-in-progress is a work of diasporic contemplation, ‘made up of the past, of my family’s past, and how it felt to always be looking back at what happened’.

Memories and interactions concerning Girl’s parents, Ma and Ikanyu, and her grandmother Ah Ma, are threaded throughout But the Girl – some loving, some emotionally tense. Yu’s portrayal of these relationships is often brutal in its honesty. As in Alice Pung’s One Hundred Days (2021), the line between Asian cultural norms and what may appear to an outsider’s eye as abuse is blurred, but Yu applies both realism and sensitivity. She is unsentimental yet tender as she sketches these contours, but the walls break down when Girl’s disparate spheres collide and a loss tilts her world on its axis.

The novel also considers the intersection of class and race, particularly within the educational setting. One key relationship is with fellow student Clementine, a ‘frenemy’ of sorts who uses Girl as a subject for her painting. It is a hall of mirrors: Clementine perceives Girl through the making of art as Girl perceives Plath through the consumption of art; through both Clementine and Plath, Girl perceives herself, making and remaking the image reflected back at her.

Microaggressions within these ostensibly progressive social circles place Girl as a perpetual outsider. She feels defined by her race, even as she tries to transcend it, and the way she is perceived externally is immovable. When Clementine reduces Girl’s work to ‘diversity’ and she finally fights back, the white woman immediately bursts into tears. This interaction embodies the way in which white women can perpetuate racism through a victim complex, bringing to mind the theories laid out in Ruby Hamad’s White Tears, Brown Scars (2019).

The 2014 setting and Girl’s relative youth at twenty-two make some of these insights seem more profound than that time or age might have realistically offered; in life, many of these lessons are gleaned with the power of hindsight and experience, and these conversations are more likely to have happened in the last five years. But in giving her protagonist such a vivid interior dialogue through first-person narration, Yu allows the reader to access the looping and often contradictory thought patterns that might lead to these revelations, or at least sow the seeds for their later discovery.

On reading Plath’s journal, in which the author refers to herself as ‘faceless’, Girl thinks: ‘no immigrant in the West has ever thought of themselves as faceless because that would be to think of oneself as raceless’. With But the Girl, Yu offers a challenging and invigorating work of many faces.

Comments powered by CComment