- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Stanwyck's world

- Article Subtitle: A Hollywood star in composite

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

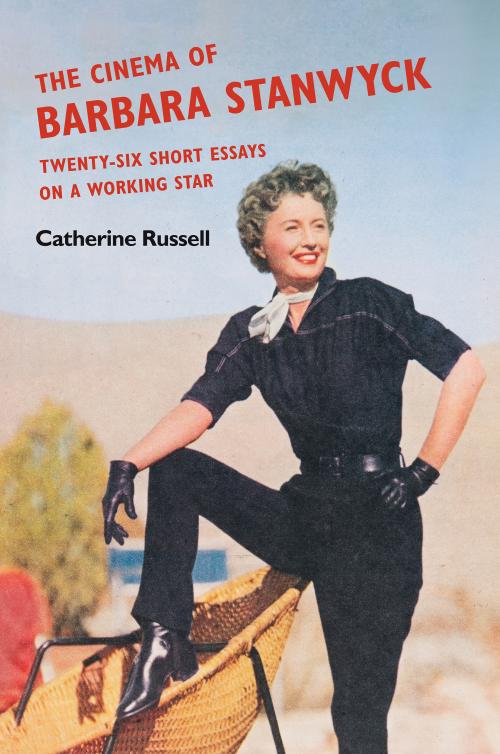

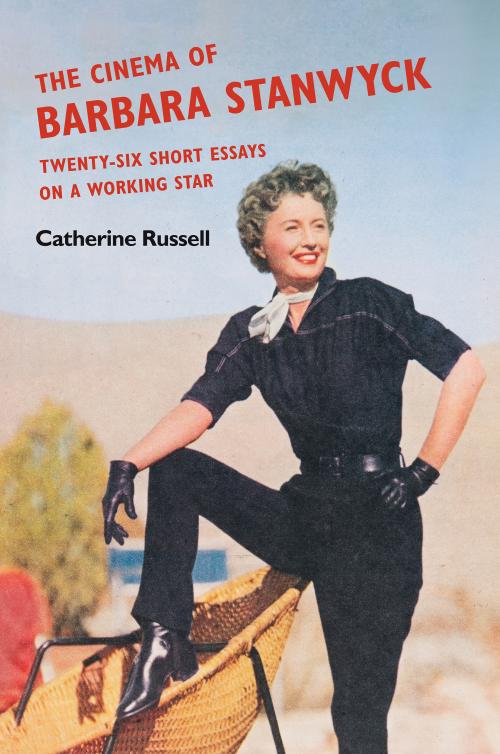

Essentially a creative critical biography, The Cinema of Barbara Stanwyck belongs to a greater project of re-examining Hollywood and decentring the phallocentrism of film history. It is the latest book in the series Women’s Media History Now! which focuses on the unexplored work of women in film. Established in 2009, this series became even more timely with the advent of #MeToo and with books such as Helen O’Hara’s call to arms, Women vs Hollywood (2021). The purpose of this new women’s media history is, according to Catherine Russell, to seek out its ‘absent’ or ‘lost’ women protagonists. Barbara Stanwyck (1907–90) may be neither absent nor lost. Indeed, as Russell admits, there is a wealth of material on Stanwyck, including monographs, biographies, and entire archives dedicated to her, and her films are still shown regularly in cinemas, on digital platforms, and on free-to-air television. Nonetheless, Russell argues that Stanwyck has been undervalued as a creative force in the films she helped make memorable. Hence the curious title of the book, which seems more suited to the study of a director than an actress. Russell sets out to show how Stanwyck ‘made’ films by making herself a master of her craft.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Felicity Chaplin reviews 'The Cinema of Barbara Stanwyck' by Catherine Russell

- Book 1 Title: The Cinema of Barbara Stanwyck

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Illinois Press, US$29.95 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Russell’s book draws on several biographies, which are combined with critical engagement with Stanwyck’s films, production notes, reviews, press articles, fan magazines, and other archival documents in an ‘interweaving of textual and intertextual storylines’. It takes the somewhat unusual form of an abecedary, a collection of short essays titled according to key words and arranged alphabetically, A through Z, twenty-six essays in all. In other words, it does not follow either of the standard formats for this type of study, based on chronology or themes. Like any star study, it blends fact and fiction, something which according to Russell merely reflects ‘the Hollywood game’ in which stars are both people and products. Stanwyck’s brand ‘was that of a tough dame, an independent woman, a hard worker, sexy when she needed to be, and with a great talent for emotional expression’. Central to the book is her unique performance style, which was particularly suited to melodrama but which could cross genres without losing its essential elements.

Russell’s book covers a lot of ground, more than can be covered in a review of this length. The essays begin with Stanwyck’s work with American auteur Douglas Sirk, with whom she made two films that, for Russell, are among her finest performances: All I Desire (1953) and There’s Always Tomorrow (1955). Stanwyck is allowed to shine in these films because, according to Russell, Sirk was able to blend character with star image, Stanwyck’s professionalism as an actor with her characters’ status as single professional women on the periphery of societal expectations of gender roles.

There is an essay on the short-lived The Barbara Stanwyck Show (1960), an anthology drama series in which Stanwyck played the central characters. The show ran for a year before being cancelled due to heavy financial losses. One of the main problems with the show, Russell notes – and it is an interesting point for a star study – is that Stanwyck struggled to be herself during the introductions to the episodes. Other essays include an examination of the ‘new woman’ Stanwyck embodied in pre-Hayes code cinema, which threw out the rule book on the kept woman trope to create women characters with ‘theories’ and a will of their own; her critical role in the rise of women-centred westerns during the studio era; an interrogation of Stanwyck as a ‘bad mother’ and her ‘abnegation of the maternal role’ in both her ‘real’ life (she was estranged from her adopted son for many years) and her film roles; and her status as ‘bachelor woman’ (something else which filtered into her film roles), which fuelled speculation about her sexual orientation, something that, for Russell, was ‘symptomatic of cultural expectations around normative femininity’ rather than grounded in any external reality.

According to Russell, in making cinema Stanwyck ‘made her own world, her own cinema in her own image, a world and an image full of contradictions’. Indeed, as one of the leading figures in Star Studies, Richard Dyer, notes: it is as a reconciler of contradictions that the star gains their charisma. Still, some of Stanwyck’s contradictions are, for Russell, harder to reconcile than others: in spite of her experiences on and off screen Stanwyck did not identify as a feminist (although here, for Russell, actions speak louder than words), and her staunch Republicanism and American patriotism make it difficult to align her with a ‘progressive agenda of feminist historiography’. Russell uses these and other more systemic contradictions – like that between women’s agency and the film industry – as justification for the ‘fragmented structure’ of her book, arguing that only in this way can such a composite and multifaceted image of Stanwyck emerge.

Comments powered by CComment