- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Talk about language

- Article Subtitle: Oxford’s way of doing philosophy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is an entertaining family biography of Oxford philosophy from 1900 to 1960. Nikhil Krishnan has mined various autobiographies and reminiscences to craft a series of biographical sketches, anecdotes, and snapshots of philosophy at Oxford during the twentieth century. He has traced the connections, legacies, and disagreements among the philosophers, demonstrating how, over the years, pupils came to inherit the chairs of the professors who had trained them, passing on certain attitudes and practices, characteristic of the Oxford way of doing things.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Karen Green reviews 'A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and war at Oxford 1900–1960' by Nikhil Krishnan

- Book 1 Title: A Terribly Serious Adventure

- Book 1 Subtitle: Philosophy and war at Oxford 1900–1960

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $28.99 hb, 392 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The earliest ancestor discussed is Gilbert Ryle (1900–76), who argued that the idea that minds and bodies are two different substances rests on a category mistake. Young enough to have avoided World War I, he ‘went up’ as the embers of the previous century’s battles between idealists and realists were waning. With a tinge of bitterness, Krishnan notes that Ryle – ‘without a post-graduate qualification to his name’ – went straight into a job at Christ Church. This was something of an Oxford pattern: Alfred Jules Ayer (1910–89), John Langshaw Austin (1911–60), Isaiah Berlin (1909–97), and Bernard Williams (1929–2003) all moved straight from undergraduate degrees into fellowships or lectureships. Even those whose careers were disrupted by World War II – Richard Mervyn Hare (1919–2002) and Peter Strawson (1919–2006) – were spared a long postgraduate apprenticeship.

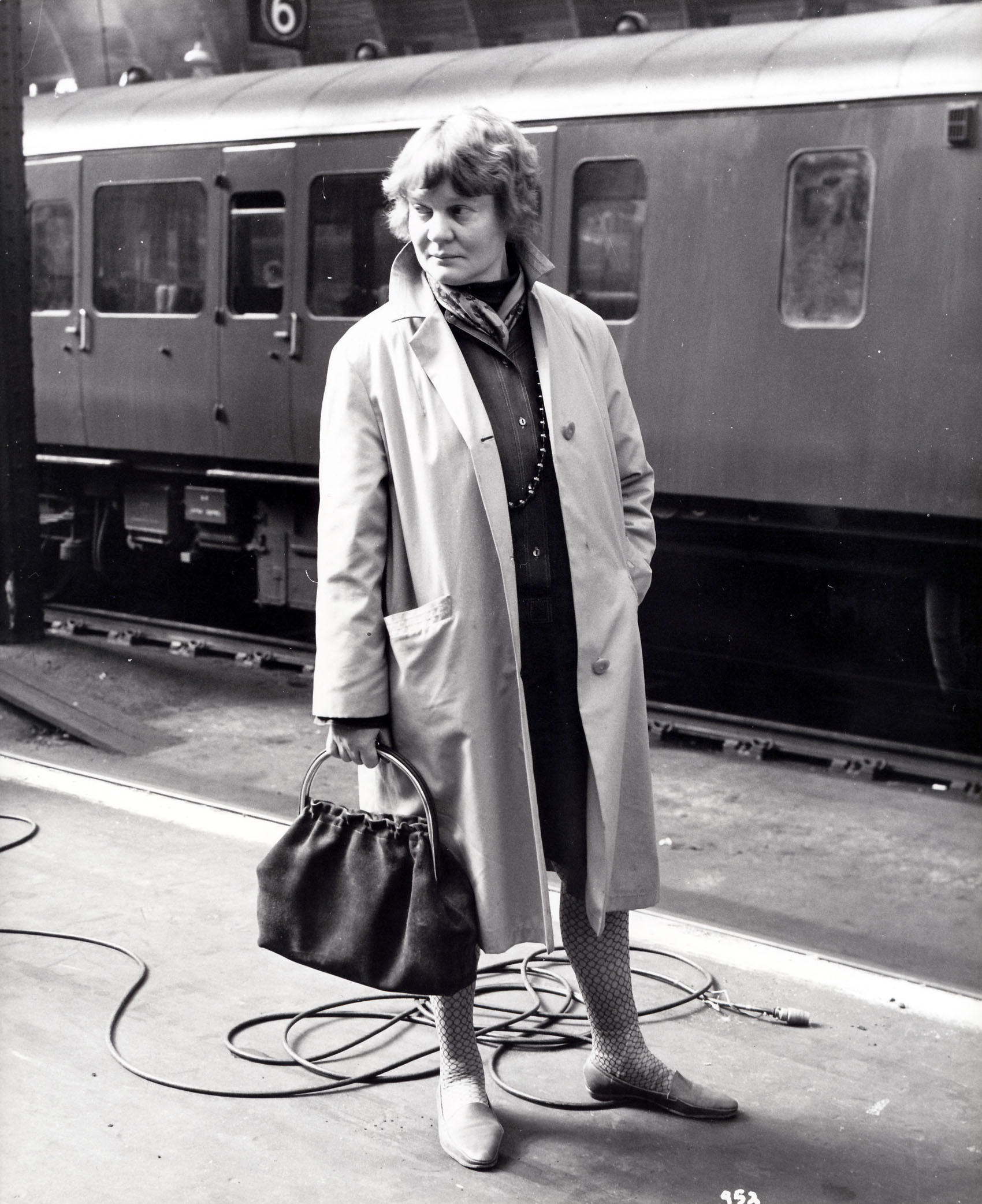

Iris Murdoch visits Paddington Station, where an adaption of her book A Severed Head was being filmed, 1970 (Winkast Film Productions Ltd/RGR Collection/Alamy).

Iris Murdoch visits Paddington Station, where an adaption of her book A Severed Head was being filmed, 1970 (Winkast Film Productions Ltd/RGR Collection/Alamy).

Ryle was influenced by G.E. Moore’s common-sense philosophy and Bertrand Russell’s logical analysis. The business of philosophy was ‘to scrape away at sentences until the content of the thoughts underlying them was revealed, their form unobstructed by the distorting structures of language and idiom’. Analysis would clear away the fog of philosophical confusion. Ayer inherited this attitude. His contact with the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle resulted in an even sharper scalpel that cut off all metaphysics as logically incompetent poetry. The excision was announced in Analysis, a journal set up with Ryle, Susan Stebbing (1885–1943), and Austin Duncan-Jones (1908–67) as the editorial committee. Positivism’s manifesto was Ayer’s Language, Truth, and Logic (1936), which developed a verificationist theory of meaning and denied the reality of the past and the existence of moral facts. Ryle had got Ayer to read Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (1921), and, after having introduced him to Wittgenstein in person, had encouraged him to go to Vienna.

Isaiah Berlin, the next relation introduced, is a somewhat distant cousin of this solidly English family. A Latvian Jew educated in London after the Bolshevik revolution, he became a Fellow of All Souls, and is most famous for his essay ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’, a defence of ‘negative liberty’, an absence of external constraint, as the only liberty worth having. Austin, his contemporary, occupies a dominant place in Krishnan’s account. On Thursday evenings from 1937, a group would meet in Berlin’s rooms, where Ayer and Austin developed their opposing attitudes. Ayer was committed to positivism. Austin began to push back against talk of sense data, moving towards the ‘ordinary language philosophy’ for which he became famous. Then World War II intervened.

A small cohort of women thus got their chance. Mary Midgley (née Scruton, 1919–2018), Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe (1919–2001) – who was married to Peter Geach (1916–2013) but never changed her name – Iris Murdoch (1919–99), and Philippa Foot (1920–2010) were lucky enough to study at an Oxford denuded of ambitious young men, so that ‘conditions were ideal for the women to speak, and what was rarer, to be heard’. A less famous beneficiary, Jean Austin (née Coutts, 1918–2016), introduced Midgley to Anscombe, who was then enrolled at St Hugh’s, while Midgley, Murdoch, and Jean Austin were at Sommerville. Oxford was dominated by positivism before the war and by ordinary language philosophy afterwards, but the women bucked this trend. They rejected positivism’s view that ethical utterances are no more than expressions of approval or disapproval. Anscombe bravely opposed the university awarding an honorary degree to President Harry Truman, a murderer, she asserted, for ordering the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Deeply influenced by Wittgenstein, whose Philosophical Investigations she translated, she thought John Austin’s philosophy a cheap simulacrum of Wittgenstein’s. With Foot and Murdoch, she initiated a return to ethics grounded in Aristotelian virtue. Later, Midgley criticised our representation of animals as ‘beasts’, drawing out the ethical elements in their behaviour and turning against the linguistic turn.

After World War II, Hare, who had survived Changi and the Burma railway, developed an account of moral statements as imperatives, offering a more sophisticated version of Ayer’s claim that they don’t describe objective facts. By the time Strawson and Williams joined the family, the original positivist traits were hardly discernible. Strawson’s Individuals called itself an essay in descriptive metaphysics, while Williams moved in the ethical direction blazed by the women.

A short review cannot do justice to the wealth of interesting detail Krishnan has collected, resulting in an engaging peek into the lives of people known mainly through their books. But the defence of Oxford as ‘concerned with the pursuit of truth through rigorous, self-aware dialogue’ falls flat. Plato thought that conversation in the Agora could uncover the truth because he believed, falsely, that we possessed knowledge before birth and could recollect it. But how is talk about the vague, ambiguous, and changeable words of natural language supposed to reveal truth? ‘Ordinary language philosophy was deadly’… and what do I mean by that?

Comments powered by CComment