- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Form, sound, address

- Article Subtitle: Manoeuvres of language and form

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

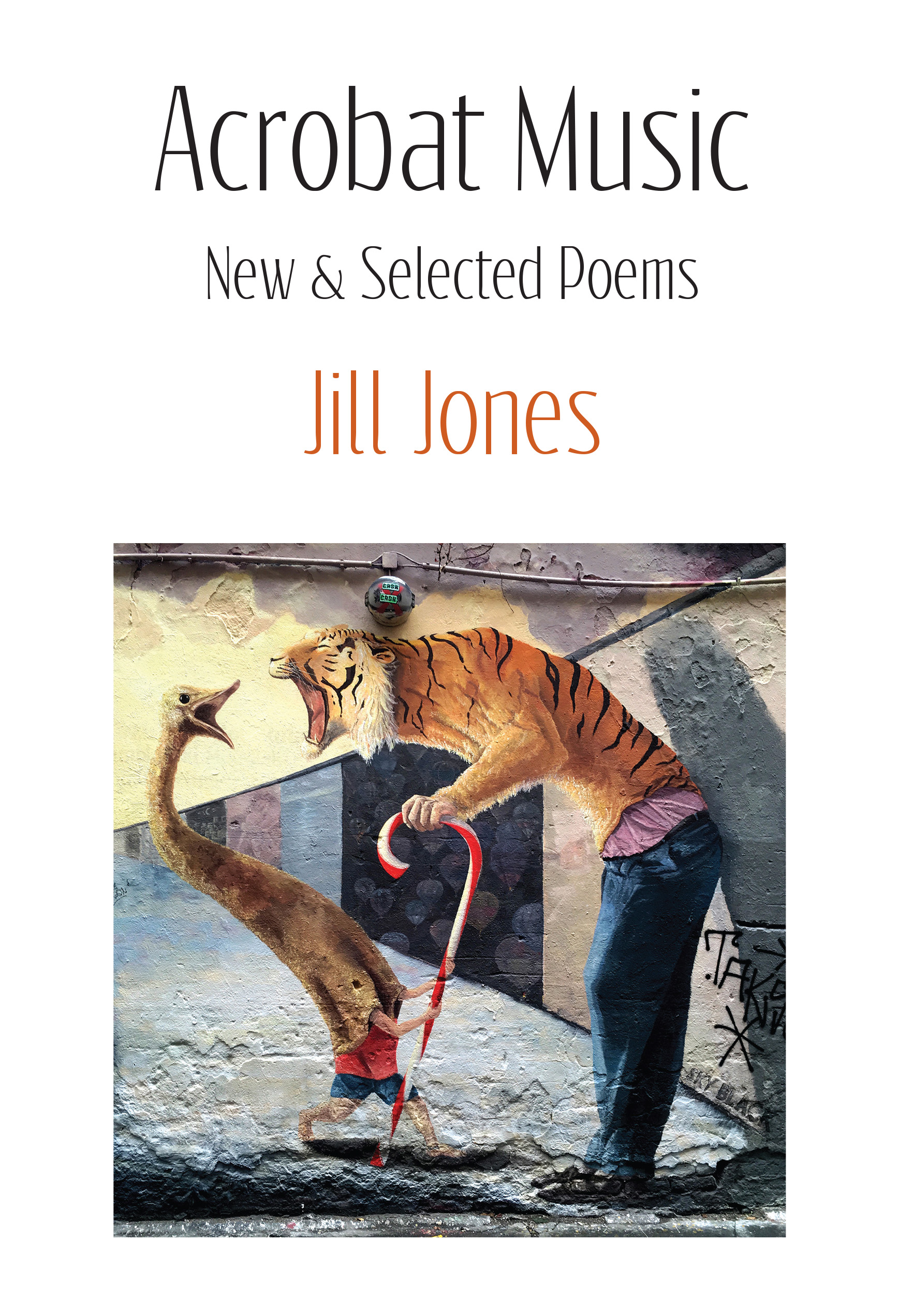

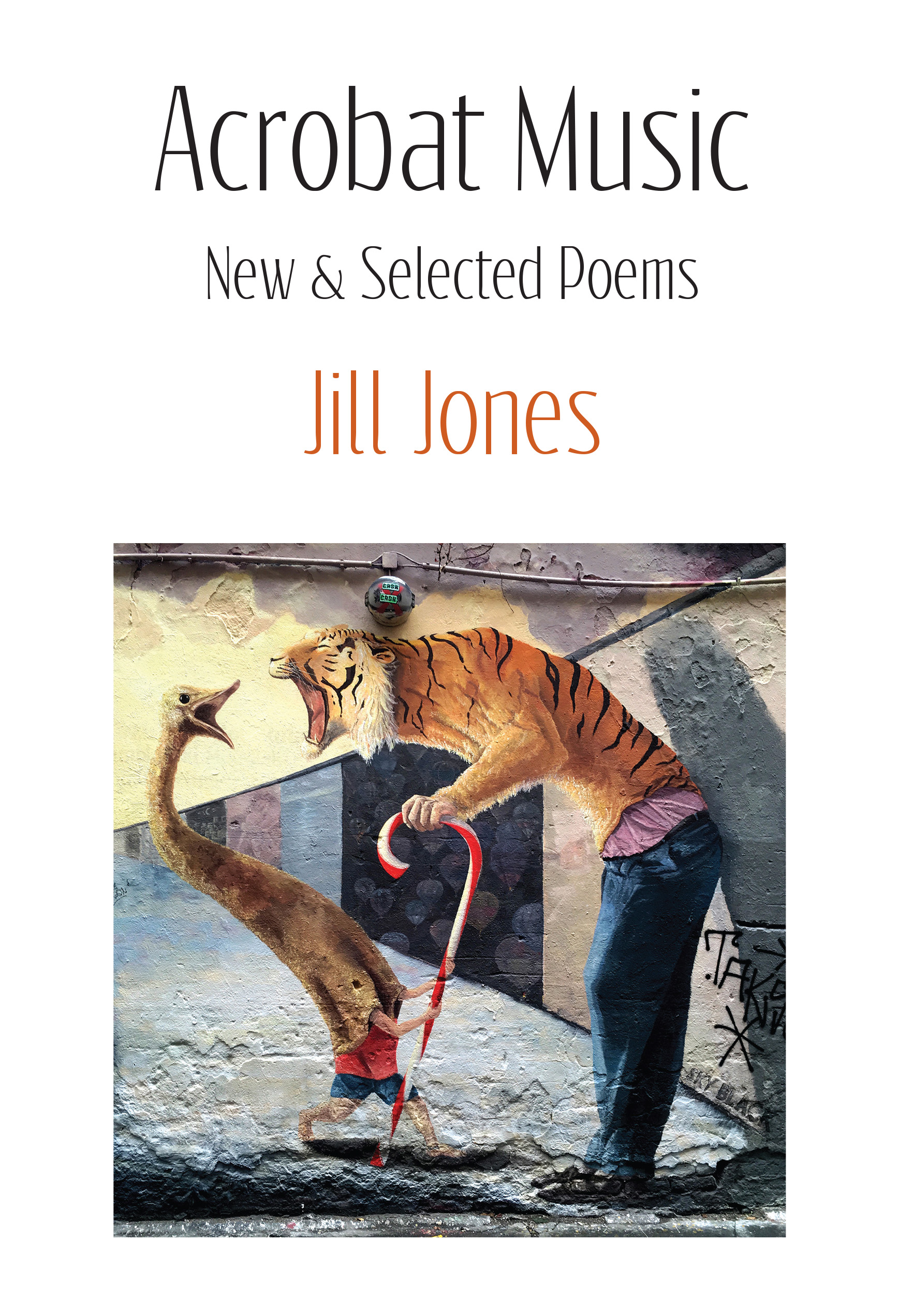

Jill Jones has given many interviews about her poetry where, inevitably, an interviewer asks her, ‘What is Australian poetry?’ In one of my favourite quips, Jones says, ‘Is it only Australians who worry about what is “Australian” poetry?’ Related issues are addressed in her pithy foreword to her second volume of new and selected poems, Acrobat Music. She states, ‘I realise, and others have said, my work doesn’t fit easily into a specified school, category or type of Australian poetry.’ This provides a fortifying manifesto to her oeuvre, reflecting Jones’s interest in ‘the possibilities of the poem … form, sound, connotation, address’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Cassandra Atherton reviews 'Acrobat Music: New and selected poems' by Jill Jones

- Book 1 Title: Acrobat Music

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 267 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is significant that some of Jones’s more linguistically challenging poems have been excluded from this volume – especially because the word ‘acrobat’ in the title suggests manoeuvres of language and form. Instead, Acrobat Music is centred on poems ‘remarked on by readers and critics/ reviewers through the years’ and poems that ‘seemed to work when read aloud’. Yet, some readers will miss Jones’s more edgy, experimental and innovative works that have partly shaped her poetic identity – primarily poems influenced by modernists such as H.D. and Gertrude Stein.

What is also striking about this collection is its eschewal of the chronological approach characteristic of most selected poetry volumes. The collection is divided into five broad ‘categories or zones’, culminating in a sixth zone of new poems, entitled ‘Not as straight as the wall / but standing, taller/ (The new poems)’. This is both liberating and disconcerting, providing new contexts in which to read Jones’s work. However, given the thrilling way the book subverts a traditional structure, it would perhaps have been even more provocative to spread these new poems throughout the other five sections. Nevertheless, at its best, the book’s structure provides the reader with compelling moments, such as in the series of poems referencing ‘blue’, that combine to form a triptych somewhat reminiscent of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. Notably, Jones’s ‘Blue’ approaches ideas of the ineffable with ‘We are thinking of the unthinkable today / as if we can’t describe the truth’.

In keeping with this assertion, this collection contains numerous poems that reveal Jones’s interest in a post-Kantian neo-sublime, exploring the anxious interstices between terror and beauty. For example, this theme is represented in the ‘new’ poem, ‘All Shook Up’, in which Jones writes, ‘You can believe in something beautiful / that’s passing’. This provides an enchainment with earlier poems such as ‘Everything is Beautiful, Finally’, which concludes with the fragments: ‘The end of the affair The last sail/ The last monster The beautiful drowning’. Furthermore, the poem, ‘Finally, Whispers!’ states, ‘With just a little science we can disturb much / in the time-space continuum / if you stay beautiful.’

Jones probing of the idea of beauty continues in her cummings-esque ‘The Beautiful Anxiety’: ‘You look where leaves hold the light / skin holds the light / edges hold the light’. Her poem, ‘The Quality of Light’ explores similar ideas about ephemerality:

Luminosity perhaps is a dream,

like travel, building, or words. It all

comes and goes, it is

as if it’s happening, at least

that’s the impression, like light

as so much fails.

This appeal to the dying of the light, sublimity and the fickleness of remembering is characteristic of a poet who restlessly and continually quizzes what she knows and perceives, and who yearns to retain a sense of light’s potency and loveliness despite her deeply felt sense of transience and, sometimes, failure.

Many of Jones’s poems tackle shifting subjectivities in beguiling ways which prioritise a sense of defamiliarisation. These include ‘mother i am waiting now to tell you’, with its witty vertical and horizonal readings; “These Things (braided)” with its entwined strands, including the vivid ‘In an ambulance you feel so alive Like a / body feels as avenues Pass’; and the lush sensuality of ‘Marrickville Sonnet’, with its exquisite final line, ‘As if heaven lies about us. Or love is brief.’ While Jones’s poetry is largely lineated, there are three inventive prose poems in this collection. ‘Futurism at Night’ demonstrates how the prose poem can house compelling internal repetition in its self-reflexive final moment: ‘Sentence searching for another – zoom, zam, zaum – as it grows.’ ‘Leaving it to the Sky’ is broken into four stanzagraphs, and includes the ironic lines ‘I don’t believe in fake tans, but I could’ and ‘So, am I famous for not being famous?’

In ‘More Than Molecules’ Jones states, ‘To grow is to be deflowered / where we are is gone is never / enough to be touched.’ Such sentiments emphasise the post-romantic tenor in Acrobat Music: New and selected Poems, most clearly manifested in her preoccupation with ideas of beauty combined with a persistent sense that language alienates writers from a connection to innocence and unmediated experience.

Comments powered by CComment