- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Wommen moste desiren’

- Article Subtitle: Chaucer’s ageless and indelible Alison

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her 2019 biography, Chaucer: A European life, Marion Turner provides a fine-grained social context for the poet’s life – from early days. Young Geoffrey Chaucer, we learn, would likely have been educated in a school such as London’s St Paul’s, with its generously stocked library, and a ‘master’ who ‘sat in a chair of authority, raised up, surveying the room’, and whose pedagogical style allowed for disputation.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Morag Fraser reviews 'The Wife of Bath' by Marion Turner

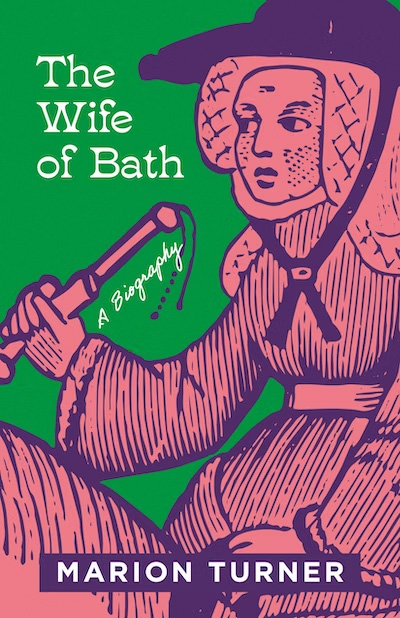

- Book 1 Title: The Wife of Bath

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, US$29.95 hb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

But a ‘biography’ of an avowedly fictional character? Turner revels in the seeming anomaly of her enterprise, taking full advantage of the six-hundred-plus-year ‘life’ that Alison, the Wife of Bath, has led since Chaucer wrote her. ‘Alison is a character whom readers across the centuries have usually seen as accessible, familiar, and, in a strange way, real.’ But, as Turner grants, as early as the second page of her Introduction, ‘Alison of Bath is not a real woman, nor was she based on a real woman, or created by a woman.’ And, more: ‘She is not even a fully rounded, psychologically complex character in the same way that, say, Dorothea Brooke or Clarissa Dalloway are’. She is a mosaic of sources, many of them male, often misogynist. But she is also rhetorically gifted, unfazed by authority, and, somehow, indelible. Turner acknowledges the seeming magic of this literary conjuring: ‘Chaucer performed some kind of alchemy when he fused his cluster of well-worn sources with contemporary details and a distinctive, personalised voice, and produced something – someone – completely new.’

It is a large claim, but Turner argues her case, in the context of English literature certainly, with vigour, and a great deal of contextual evidence. The Black Death changed life in Chaucer’s England, and in particular ways for women. Ironically, it afforded them more opportunity, more autonomy in both marriage and work. This coincided with what Turner calls Chaucer’s ‘pioneering way of exploring narratives of the self’.

Elsewhere, Turner argues that ‘[w]hen he was creating Alison as a character, Chaucer’s own skill and inspiration were powered by literary sources and by his historical environment, but the character came to full being in the mind of the reader.’ I wonder. When I went back to reread my battered 1957 edition of F.N. Robinson’s The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Alison sprang to pulsing life again, in ways that I found as challenging and confronting as I did when I first met her. But it was Chaucer’s poetry, vivid and particular as Giotto’s paintings, his rhythms, that vernacular vivacity and audaciousness, that conjured the irreducible character, the ‘full being’, that is Alison. (And they prompted a minor irritation: in a copiously annotated book, could not the publisher have found space to print ‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale’? The book is a feast for general readers, but not every general reader has Chaucer on her shelves.)

Publishing quibbles aside, Turner’s ‘Biography’ is an incisive examination of a tumultuous historical period, its literature, and its startling connection with, and importance for, our own time. It is written with a zest and pace that befits its subject. Alison is a provocateur. She is disruptive, she threatens norms and preconceptions – about gender, propriety, religious strictures, beliefs, marriage, rights, equality – even now. (I kept being reminded of Germaine Greer and early responses to The Female Eunuch.)

Alison’s ‘Prologue’ is an unbridled performance piece by a woman who has lived, learned (‘Experience… is right ynogh for me’), worked, travelled widely, married (five times), been widowed, beaten, deafened, who has disputed authorities, been reconciled in love (perhaps) and who has finally assumed ‘soveraynetee’. Her ‘Tale’ is about rape, power imbalances, youth and age, and what ‘wommen moste desiren’. But before she can tell it, Alison is forestalled by a Friar and a Summoner (an official empowered to bring people before ecclesiastical courts). The Pilgrim’s ‘Hoost’ and Chaucer figure routs the pair with a command: ‘Lat the woman telle hire tale.’ And, unbowed, Alison does.

The ubiquity of rape, and the liberty to tell one’s tale, however scandalising: these are not conventional expectations of writing about Geoffrey Chaucer. But Chaucer has always been strong meat, censored, and traduced by writers from Dryden, Pope, and Voltaire to the legions of scholars who have corralled him in philological or other silos. Turner exempts Shakespeare and James Joyce (imagine dinner with Alison, Falstaff, and Molly Bloom), and does us a grand service by highlighting the work of contemporary writers (like Zadie Smith in The Wife of Willesden) who have taken Chaucer’s creation whole, and have set us all dancing again with Alison of Bath ‘in a wild exchange of energy, passion and ideas’.

Comments powered by CComment