- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Body and home

- Article Subtitle: The grain of the domestic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sharon Olds, author of twelve poetry collections including the Pulitzer Prize-winning Stag’s Leap, has said that when she wrote about motherhood forty years ago, she was advised by editors (‘very snooty, very put-me-down’) to try Ladies Home Journal. For Olds, now celebrated as a bold poet of the body, there is some Schadenfreude in the anecdote, like Bob Dylan’s in ‘Talkin’ New York’ as he recounts his arrival in New York, ‘blowin’ my lungs out for a dollar a day’, only to be told ‘You sound like a hillbilly / We want folksingers here.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Felicity Plunkett reviews 'Spore or Seed' by Caitlin Maling and 'Increments of the Everyday' by Rose Lucas

- Book 1 Title: Spore or Seed

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $29.99 pb, 127 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

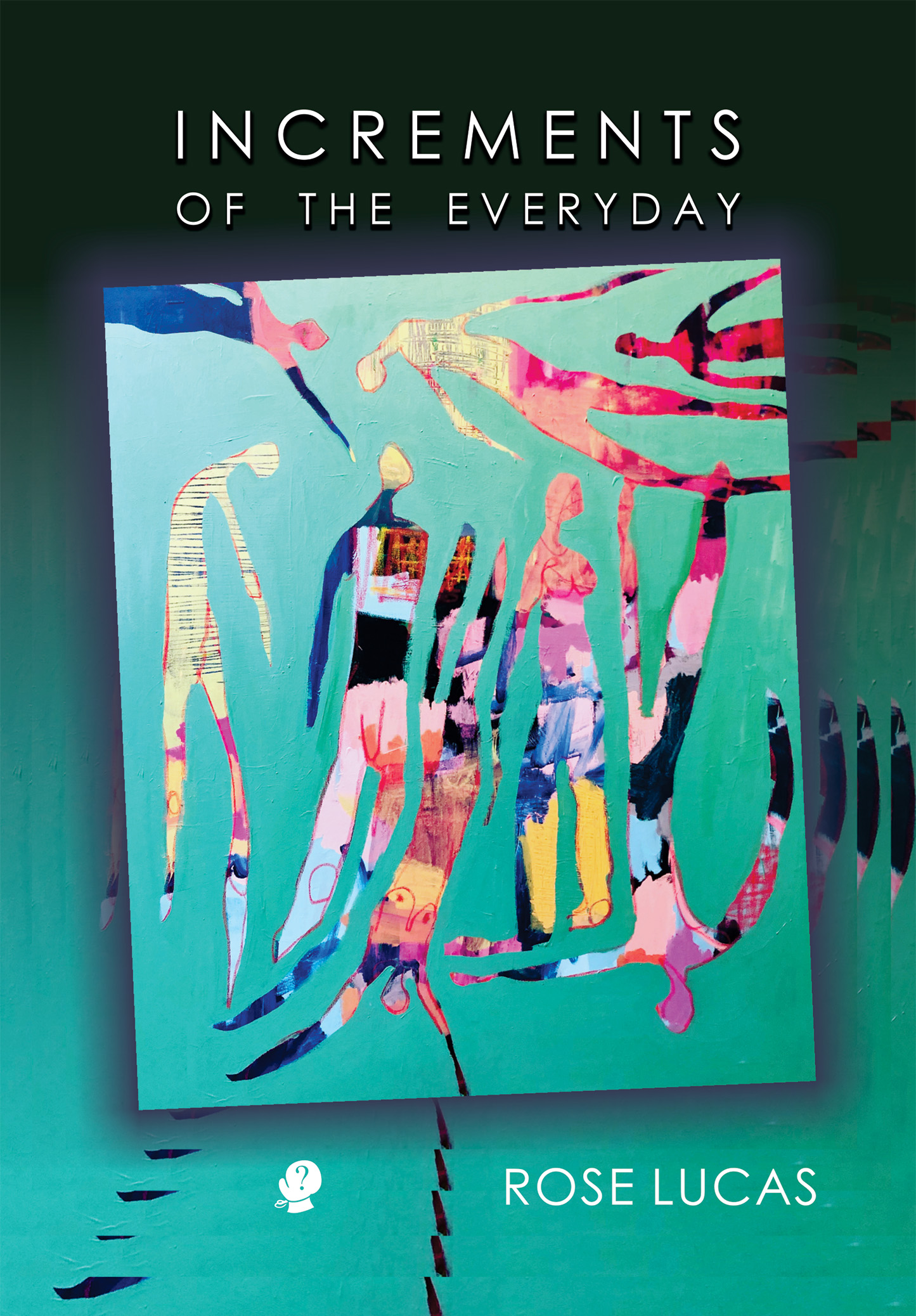

- Book 2 Title: Increments of the Everyday

- Book 2 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 103 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

When, in Caitlin Maling’s fourth poetry collection, Spore or Seed, she writes: ‘The poetic field rarely has children in it, often gods, often desire’, she remains part of a vanguard, along with Rose Lucas, whose Increments of the Everyday is her fourth collection too. Each writes about the grain of the domestic and being a mother, the shapes and shades of reciprocity, the body and home.

Maling often works with husked lines, a brisk tone, and syntax pitched towards accuracy. There is an acerbic, unsentimental, even anti-sentimental tone. This signature of Maling’s shrewd work may also contain a nod to that history of gendered admonition.

The book’s second section ‘In Process’ comprises elastic lines. Small prose paragraphs abut blunt lines to produce a compact lyric essayistic effect. It begins with an observation of the abstract – ‘The question of form arises’ – and opens into the corporeal. At first the question itself is the subject, but as the speaker becomes agent and subject, active verbs like ‘clutch’ and ‘grow’ multiply. As her body alters to accommodate the foetus’s development, the poem builds its heft. By the end there is gristle, wound, flesh, bone, and scar tissue.

‘In Process’ is partly about the changed syntax pregnancy brings. Early lines signal a sidelong ars poetica: ‘[t]he constant momentum of being a staging ground for growth’, ‘the tension of a curve, the sharp under the smooth’. Up through the lines’ surface pop images of the pregnant body and growing child, as though the stanzas themselves embody a quickening, the sudden flutter of a child’s movement in utero.

Many poems are addressed to the child, and carry questions of intergenerational trauma and inheritance. ‘One day,’ the speaker writes in ‘A Measured Risk’, ‘my father left me / I cannot say / yours will not / do the same.’ Maling’s diction is often spare. In ‘In Bed’ the speaker states: ‘I cannot / put it plainer / than that.’

In visceral breastfeeding poems, the spectre of mastitis tingles and flickers. This incorporated coexistence of the more-than-human with the human, this theme of enmeshment, is part of Maling’s larger ecological project, as in her previous collection Fish Work (2021), shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Poetry, which examines the Northern Great Barrier Reef.

The child worries the edge of self and other and the breastfeeding speaker becomes ‘an aquarium / for the fronds of bacteria / floating through’. The foetus is ‘tumbleweed / looking for a ditch to stick’. ‘Tangle of metaphors’, Maling thinks, possibly nodding to the rich thicket of similes in Plath’s birth poems such as ‘You’re’, where the baby emerges ‘Right, like a well-done sum’. As a device, metaphor suggests that one thing may be another; may never simply be itself.

Ideas of self and other are also central to Increments of the Everyday. It begins with a quiet ‘Hiatus Diary’. These lockdown poems document the interval where human lives contracted as Covid-19 began its worldwide expansion. The namelessness of the exact threat pulses through the poems as the word ‘something’. ‘Something is proliferating,’ Lucas writes in ‘Anxiety’, ‘something terrible is swirling / under our closed windows’ (‘Isolation makes me’). Eventually ‘something’ becomes a transformative agent: ‘isolation makes me … something … different’.

The pauses between words restrain the pace of the poems. ‘Year of Breath’ alludes to ‘this respiring machine’, pursued by a ‘choke of tightness’, the ‘always risk of / catch’. These measured, steady, and attentive poems about suburban pandemic life shudder into another register in ‘Impossible: a grief cycle’, written after the death of Lucas’s young friend, Sophie Ellis. Lucas uses the first person in ‘Pietà’ in a poem dedicated to Ellis’s mother addressing ‘Child of my blood and sinew’. This inhabitation of the ‘I’ poses poetic questions that Maling’s poems also explore, about who hosts whom, questions examined by critic J. Hillis Miller in his essay ‘The Critic as Host’ (1977), which posits texts as both host and guest, sharing a reciprocal bond like the body’s with parasites.

As Lucas reflects on loss, accusatory dishes accumulate to be washed (their washing a spiritual practice) and the kitchen table sits with its ‘accretions of intent and carelessness’. Memories arise, like the glimpse of a father figure at a petrol bowser, for a moment abandoning his ‘precious cargo’. With another jolt out of reverie, the collection’s final section meticulously documents a fall and subsequent medical care, leading back to the questions of reciprocity and responsibility both collections parse.

Lucas’s book ends with the body settling. Mending nerve and tissue hold the measure of in- and out-breath, of passing time and letting go, a ‘mosaic of passing moments’. Maling’s, restive, arrives at the earth’s invitation to consider ‘compost, decay; what can be so / and what floats out to sea’ as a child arrives, blazing into an endangered world, ‘flame among flames’.

Comments powered by CComment