- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'The song of null land'

- Article Subtitle: The poetics of disorientation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In a world both foul and fallen, where delusion, death, and unassailable Dummheit seem to wait on every corner, what can poetry do that warrants our rapt attention more than every other kind of distraction? Justin Clemens voiced the common lament when he wrote, ‘No-one reads poetry anymore, there being not enough time and more exciting entertainments out there.’ The issue, he said, is ‘a materialist problem that has always proven fundamental for poets: how to compose something that, by its own mere affective powers alone, will continue to be read or recited’ (‘Being Caught dead’, Overland, 202, 2011). That clinches the dilemma rather well. And yet, entertainment or not – and effective or not in their affective power – poetry collections seem to endure as a place, of Lilliputian dimensions, to encounter other worlds and world views.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Judith Bishop reviews 'The Book of Falling' by David McCooey and 'A Foul Wind' by Justin Clemens

- Book 1 Title: A Foul Wind

- Book 1 Biblio: Hunter Publishers, $24.95 pb, 104 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

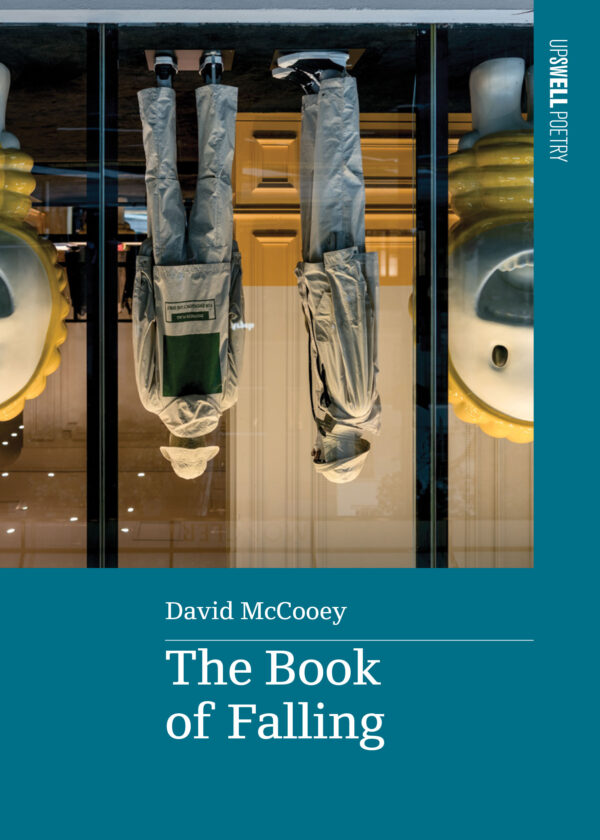

- Book 2 Title: The Book of Falling

- Book 2 Biblio: Upswell, $24.99 pb, 112 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

If representational meaning is off the table here, emotive meaning slides into its place, underscoring the black humour with recurring tropes and jokes about putrescence, orifices, money, death, escape, power, illusion, hype, ruin, abomination, and exhaustion. A hallucinatory, David Lynch-inspired opening poem, ‘the problem of evil’, sets the scene by DJ’ing a sequence of four genre snippets in as many stanzas, one of which reads like a punk rock lyric: ‘All doing / Is a death ray / To fuck the one you love.’

Dizzying lexical and dialectal mash-ups thumb their nose at the conventional lyric conflation of identity and language, offering in its place a style driven by the accidents of ‘stochastic metaneuronic discharge / and exhaust’:

Ah he wuz well rewarded later wit

a million books he couldna read, so

it’s hard to feel too sorry for the impersonal personage

he felt himself.

(‘Mentaphonic radiocules enwinkling ordographic

delicacies outta insalubrious oncophores’)

The final section, ‘Home of own’, which comprises half the book, is energetically and tonally distinct from the rest, though many of its lexical moves are the same. Spoiler alert: ‘Home of own’ is a near-homophone of – well, you know what. Lacking the rewards of exuberant lingual energy, this extended play on philosophical conceptions of language, naming, and being falls rather flat, with the effort of deciphering lines such as ‘One a mat, a peer / and a lurgy. / I, runny, / Lie to tease’ offering little even to the most ardent lover of homophony.

And yet, there are arresting lines here, though one hesitates to read them as transparently sincere: ‘so many prophets of hate / hate needs no prophets’.

David McCooey’s fifth collection, The Book of Falling, opens with a section on other creative lives. Here is the poet voicing over Elizabeth Bishop as she contemplates her imminent move to Seattle:

Underneath us all, the heavy, red earth keeps faith

with the human structures built upon it,

[...]

Meanwhile living things spring and decline,

in their godless and Biblical manner.

(‘Questions of Travel’)

‘Fleeting’ imagines Sylvia Plath, having lived fifty years past her death at the age of thirty, finding life again after ‘the deranging noise’ of poetry and ‘the brief duration of abysmal sleep’.

Elsewhere, McCooey’s poems can be oneiric in their understatement. In the serial poem ‘Chamber Pieces (ii)’, the unremarkable becomes the revenant:

We are at a dining table.

The window looks out onto bush.

Someone remarks on the view.

‘What is a view?’ I ask.

My father gestures with his hands.

I look outside at the unfamiliar trees.

A number of the poems reveal a disjuncture between human frailty, including depression, and the many cultural frames (movies, interviews, and theme parks among them) that urge and compel our energy and involvement. ‘Extracts from an Interview’ points to this as a common artistic experience (On the Beach was famous as a comedown from earlier successes):

Q. How do you feel about critics?

After the downpour

my son puts on an LP:

Neil Young’s On the Beach.

Joining an increasing number of books that use the cognitive ricochet between word and image to strong effect, a section titled ‘Three photo poems’ invites us to parse that space for various sorts of disconnect. The lines in ‘Posing cards’ read as directives to a photographer (‘Have the couple half hug / with their arms crossing in the front’). The words underline the parents’ estrangement with instructions on how to create the false impression of a close-knit family. (Later in the book, ‘A Brief Family History of Falling’ touches on a fall that may have led to their marriage: ‘He was a broken man, and she felt sorry for him’). In ‘Bathroom abstraction’, photographs of bathroom tiles foreground the inhuman indifference of their surface, while the words limn the vulnerability of human bodies trying to keep it all together in post-operative, post-partum, and foreign bathrooms.

In her critical work The Lyric in the Age of the Brain (2016), Nikki Skillman proposes that lyric and anti-lyric modes are less distinct than their proponents might imagine, at a time when materialist, somatic, and neurological thinking are increasingly sources for both kinds of poets. The Book of Falling substantiates her thesis with a neurological poem, ‘Synaptic Transmissions: An Elegy’. Here, the dead father ‘becomes real in a human sense’, in the neural reconstructions of presence that memories are. There is comfort in the bodily traces of intimate connection that continue in the brain:

Now he is heavy as a thought

distributed in the deep

sediment of my memory,

in the uncanny articulation of a gesture,

a signal from a dying star.

If McCooey’s book keeps faith with the representational mode and affective powers of contemporary lyric, Clemens’ is a vigorous exemplar of the anti-lyric mode. Both move through the maze of biological and cultural disorientation and emerge with a poetics that deserves our undistracted attention.

Comments powered by CComment