- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Escaping the barriers

- Article Subtitle: Debunking myths about women in science

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

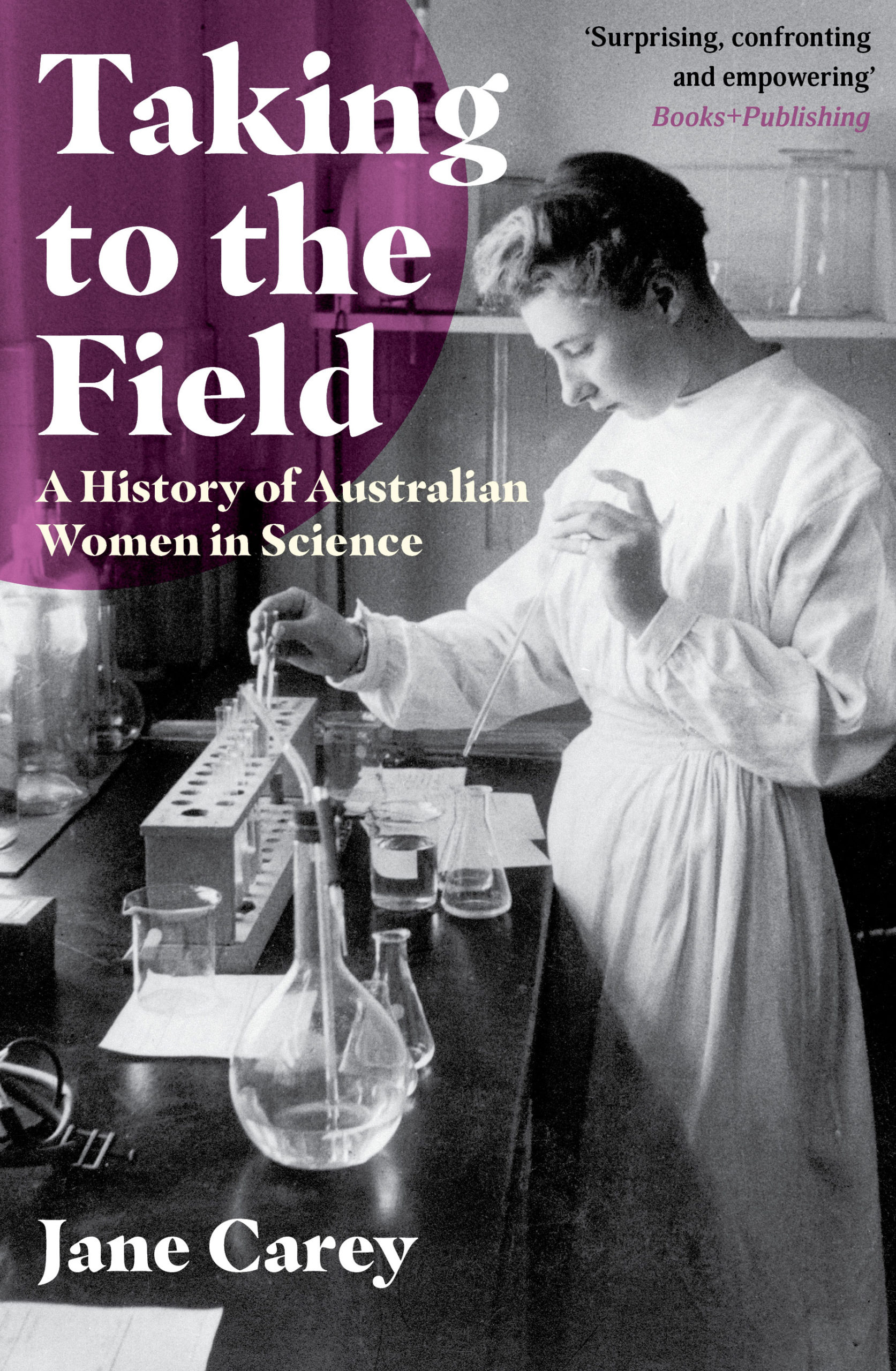

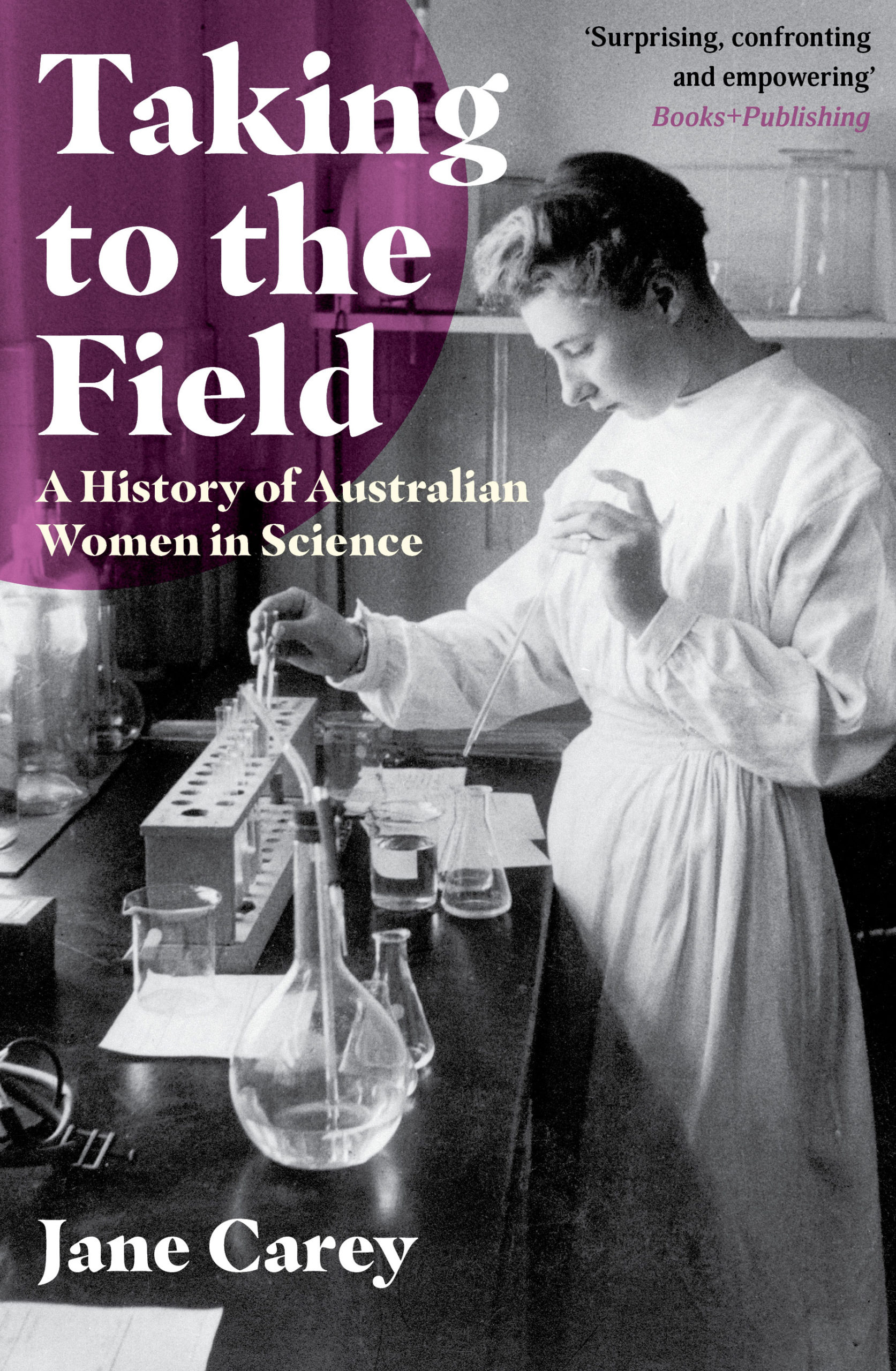

In 1943, of the 101 science graduates of the University of Sydney, 55.4 per cent were women. That same year at the University of Melbourne the proportion was 46.2 per cent, and by 1945 women made up 37.4 per cent of all science graduates across Australia. Given contemporary anxieties about women’s involvement in science, these statistics appear unbelievable. Yet, as Jane Carey explores in Taking to the Field, between the 1880s and the 1950s women were not only completing science degrees in notable numbers but, even outside the unusual war years, were contributing valuably to Australian science through research, teaching, and social reform.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jessica Urwin reviews 'Taking to the Field: A history of Australian women in science' by Jane Carey

- Book 1 Title: Taking to the Field

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of Australian women in science

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

But women’s participation in science expanded beyond amateurism. Once Australian universities opened their doors in the 1880s, the prohibitive cost of undertaking a degree and the inaccessibility of good secondary education prevented many from entering universities. Those that acquired bachelor degrees were part of an élite group. Women were not naturally excluded from this. To the contrary, women’s admission to science degrees existed as an example of Australia’s progressivism at the turn of the century, especially in comparison to the staunch tradition of Oxford and Cambridge, whose first women graduates received their degrees in 1920 and 1948 respectively. And while the number of graduates in science was still remarkably low, Australian universities were openly proud of their ‘sweet girl graduates’. These were women whose scientific pursuits seemingly placed them ‘above ordinary feminine trivialities’, while paradoxically representing the compatibility of scientific work with ‘traditional feminine activities’ as specimen jars were likened to ‘the thrifty housewife’s jam jars’.

Reading Taking to the Field, it becomes clear that women were invaluable to science not only as university students, but as educators. It is in this context that Ada Lambert became the first woman to be appointed a university lecturer in 1899. And while few other women would achieve similar permanency over the succeeding decades, university departments were heavily populated by women. Walter Baldwin Spencer’s biology department at the University of Melbourne became entirely dependent upon women as researchers, tutors, and demonstrators. This was certainly not an anomaly; the lack of career prospects in science made it an unpopular pursuit for men. The shortage of jobs also ensured that many scientifically trained women turned to secondary teaching or even scientific social reform, the latter influenced strongly by eugenics. Regardless of the space they occupied, Carey maintains that these ‘pioneering’ women demonstrated their ability to overcome many of the obstacles of gender in this period.

Yet, gender still mattered. A key enabler of women’s early inclusion in science was men’s absence. In the early twentieth century, senior male biological scientists lamented the abundance of women applying for vacant positions; considerable effort was put towards attracting men to science, not least by increasing salaries. Women, seldom promoted beyond casual positions, were often forced to give up their research careers following marriage. Nepotism was forbidden by many universities; while daughters of famous scientists (such as Douglas Mawson’s, Patricia and Jessica Mawson) were able to follow their fathers into science, women could not be gainfully employed by their husband’s institution. Naturally, this precluded many educated women from employment.

But it was the masculinisation of science following World War II that most acutely impacted women’s participation. The importance of science to the war effort resulted in a remarkable growth in male university enrolments. By the 1960s, academia was rebranded as an unwomanly pursuit, ‘at odds’ with women’s ‘feminine appearance’. Biology, where women had found a safe haven, was recast as a man’s domain. Women were actively paid less than their male counterparts and some universities forced them to retire earlier than their male colleagues. Unsurprisingly, the percentage of women science graduates dropped considerably, contributing to what Carey considers our contemporary presumption of ‘the impossibility of women scientists’ in the early twentieth century.

Challenging this presumption, Taking to the Field reiterates that women’s contemporary participation in science is not a teleological tale of progress, from absence to inclusion. Rather, it is one of ebbs and flows. By highlighting the enigmatic and unique women who participated in Australian science during its early days, Carey demonstrates that their contributions have been vastly underappreciated by historians. This has been to our detriment, not least as their stories unsettle our understandings of women in science as a markedly contemporary – and exceptional – development. In exploring the historic contributions of women to Australian science, Taking to the Field confronts contemporary anxieties about the place of women in the field by demonstrating that it has not always been – therefore does not have to be – hostile to women.

Comments powered by CComment